TRAUMA TRAUMA Trauma Informed Care RESILIANCE DISSERTATION DEFENSE A PROFESSIONAL LEARNING COMMUNITY FOR DEVELOPING TRAUMA-INFORMED PRACTICES USING PARTICIPATORY ACTION METHODS Transforming School Culture for Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disabilities Jacob Campbell, LICSW CIIS - Transformative Studies Department Friday, March 3rd, 2023

Slide 1

Slide 2

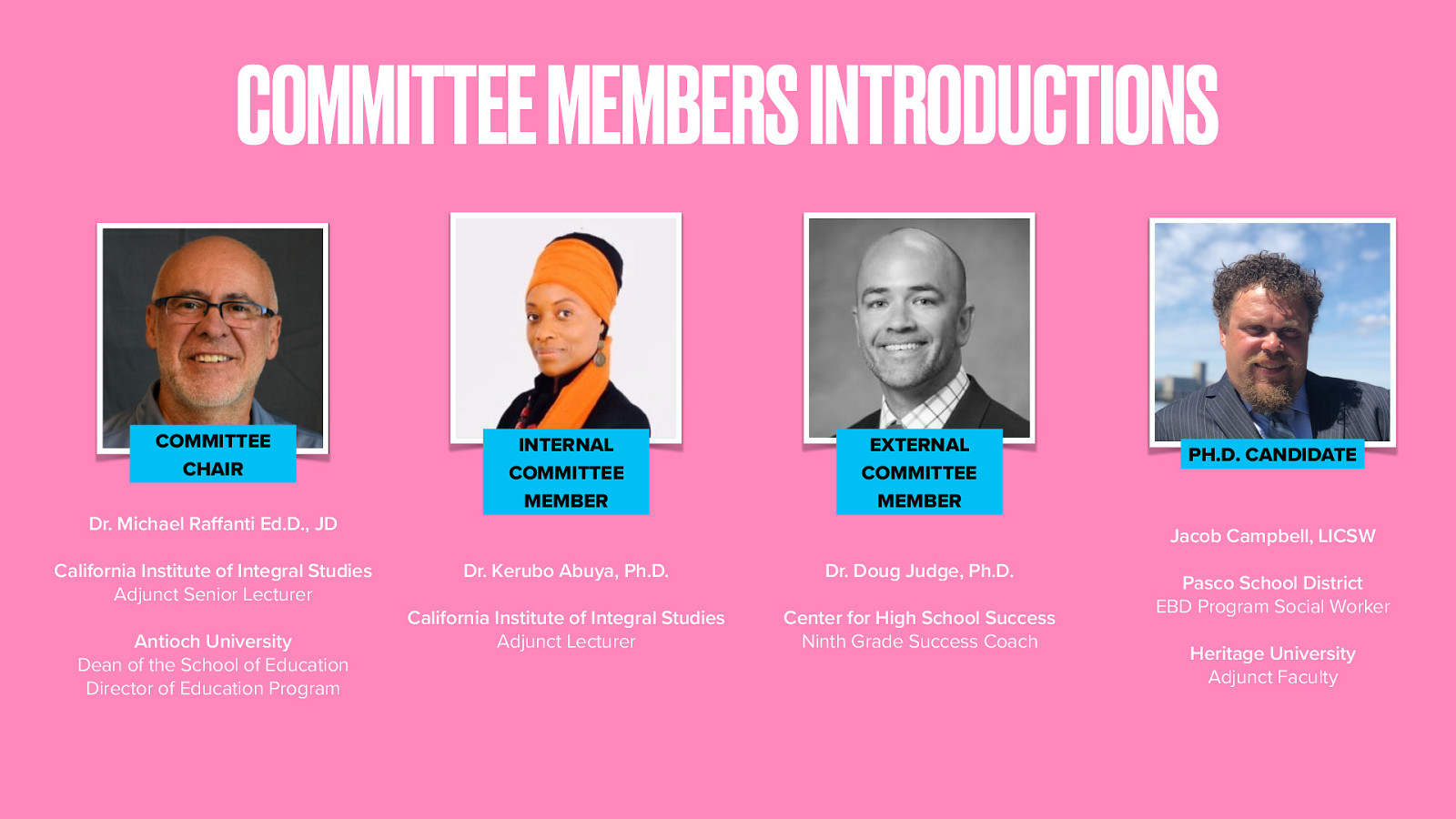

Committee Member Introductions

Michael, you really have been my magnifying glass, as you have helped me to focus my work and the development of this research process Kerubo, you have really been an open book for me, supporting me as I learn and grow my skills and ability at engaging in participatory action research Doug, you have been my map as you have encouraged me to consider some of the why and deeper ideas how we can support our students.

Introduce each of them… talk about work, research, etc. See slide as well

Slide 3

Potential Agenda

Committee members introductions Oral defense

- Problem statement

- Research question(s)

- Theoretical framework

- Overview of research

- Connection of research questions and activities

- Limitations

- Discussion of results Committee member responses (questions or concerns) Committee deliberation

Slide 4

Problem Statement: The Impact of Trauma on Students

I want to start with talking briefly about the basis of my research, that trauma is frequent in schools and has a significant impact on students.

Over the years I have worked with kids with all manner of difficulties and challenges. I’ve worked with students attempting to leave gang life. I’ve worked with survivors of verbal, physical, and sexual assault. I’ve worked with youth and adults who are refugees. I’ve seen the aftermath of the genocide that took place in Rwanda…

With the global pandemic, increasing mass violent crimes, and a higher level of interconnectedness and sharing of traumatic events, there are many ways we can see another trauma as impacting all of us…

The Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative (2014) defines trauma as:

Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being. (p. 7, bold in original)

- One commonly discussed metric of talking about trauma is understanding Adverse Childhood Experiences or ACEs. So, we know that trauma is very frequent. Bethell and associates in 2017 report that just under half (46.3%) of youth in the United States have one or more ACE

- Not only is it frequent, but the more ACEs a student also has, the more likely they are to have emotional, mental, or behavioral conditions. (Bethell et al., 2016)

- We also know that trauma and related experiences are disruptive to students’ academic and social skills. It can impact their cognitive, academic, and social/emotional/behavioral functioning (Perfect et al., 2016; Trout et al., 2006)

Slide 5

Intersectionality for our Students

Intersectionality for our Students

I want to briefly mention the great deal of intersectionality that often occurs for these students.

- It connects with what Van Der Kolk (2015) argues for the inclusion of developmental trauma disorder in his book the body keeps the score (which we will talk more about).

- Often there are connections with race/ethnicity and socio-economic status

- Many of our students have interactions with the juvenile justice system (I was just having a conversation with the teacher in my classroom…) and the school to prison pipeline

- Disability is multi-faceted for our students and can impact them in many ways

- COVID-19 has also been a global traumatic experience

Slide 6

Problem Statement: The need for trauma-informed practices

This leads us to the argument for the need for trauma-informed care practices. What is trauma informed-informed practices and why do we need it? The SAMSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative (2014) again defines Trauma-informed as:

A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization (p. 9, bold included in the original text).

The need to implement trauma-informed care includes the following principles outlined by Cavanaugh (2016):

- Students who have experienced trauma need school to offer a safe and consistent environment

- Staff should put a particular focus on having positive interactions with the students

- Teachers should implement a culturally responsive practice within their classroom that offers peer interaction and connection and uses a strengths-based approach.

Slide 7

Problem Statement: Challenges for teachers serving students with EBD and compassion fatigue

My research focuses on a specific group of school staff, those who work with some of the most severe and behaviorally challenging students. These students are ones who often qualify for special education services under the categories of emotional behavioral disabilities (EBD), or who have special health care needs. These students experience an increase in concerns related to ACEs. Kan et al. (2020) describe that they have disproportionately higher rates of ACEs compared to their non-disabled peers. Some of the categories that are more likely to impact these students include: living with someone with mental illness, witnessing domestic violence, and witnessing or being a victim of neighborhood violence

We also know that students with disabilities and students of color experience marginalization based on access to quality instruction, school disciplinary practices, and special education placement practices (Scherr & Mayer, 2019). And minority students are disproportionately identified with EBD by schools (Bridget et al., 2016; Tefera & Fischman, 2020).

In classrooms that serve these students, there seems to be a higher level of compassion fatigue and burnout.

Ziaian-Ghafari and Berg (2019) used compassion fatigue as a lens to understand the psychological distress that teachers experience working within special education.

Hoffman et al. (2007) connect the concept of compassion fatigue to understand burnout among special education teachers.

Bettini et al (2019) showcases how schools experience difficulty retaining special educators to serve students with EBD

All of these problems are concerns that need to be addressed in our schools.

Slide 8

The Professional Learning Community

One of the ways that schools have been working through processes of school reform include the use of Professional Learning Communites (PLCs). Hord in 1997 describes some of the characteristics of a PLC. These include:

- supportive and shared leadership

- collective creativity

- shared values and vision

- supportive conditions

- shared personal practices

PLC’s have been broadly adopted of to enhance schools. But they are almost always focused on academic and curriculum needs. There are limited examples of them being used for increasing learning for topics such as social-emotional learning strategies.

Slide 9

Using a PLC to deliver professional development for trauma-informed care

The majority of training and professional development around social-emotional learning is implemented through more traditional methods of professional development. These are most often through workshop-style training. These can be productive, and I would still argue are needed. My research seeks to find an avenue for professional learning and school reform that can be democratized for learning about trauma-informed care. I think there is a space where topics such as social-emotional learning or trauma-informed care practices can be a part of the staff’s cycles of inquiry used within PLC. There are some related examples of this:

- Johnson (2018) describes that a PLC provides a safe environment where school staff can discuss social-emotional learning competencies and it can be meaningful for staff

- Leonard and Woodland (2022) used their PLC to consider social-emotional learning and promote anti-racist ideals.

- Reflection and being able to learn from reflective action is becoming considered integral in educational research. (Webster-Wright, 2009)

There has been a lack of examples of the PLC being used to support the development and implementation of a trauma-informed classroom or school setting

This gap in the research is where I have situated my study.

Slide 10

Theoretical Framework

In explaining my research, defining the theoretical framework I was focused on is helpful. First, I grounded my research through a process of systems thinking. Stroh (2015) describes that systems theory helps us to change the things that matter the most. When I describe the clear and worthwhile change, this critical thinking helps to determine it through:

- The co-researchers and I use systems thinking to help identify and connect to these often unrecognized elements.

- The patterns that emerge from these connections often follow archetypes that help us understand the interactions of the parts of the system.

- We will follow the conditions that help facilitate collective impact, such as building a common agenda, determining a shared measurement, and nurturing continuous communication, which are conditions of collective impact (Stroh, 2015)

A significant purpose of the dialogs we will be participating in is to engage in transformation. The transformative paradigm has PAR fit within it, as one of its primary intentions is to be transformative (Mertens, 2009)

My co-researchers and I sought ways to transform ourselves, our classrooms, and our schools… and talk about how we can share trauma-informed care beyond our group. This required leadership development and processes to implement.

Along with considering how to support our students best, I wanted to develop the staff engaging in developing them through a Montuori and Donnelly (2017) describe transformative leadership as a framework that lets us understand that leadership can be acquired through emergent processes. It also views it as paradoxical and allows for plurality in how it is embodied.

Slide 11

Research Question

That leads us to what the my actual research question is:

This inquiry seeks to determine whether a PLC focused on trauma-informed care practices can create clear and worthwhile change for teachers serving students with EBD and subsequently impacting their classrooms and schools through a participatory action research methodology

Slide 12

Sub Questions Being Researched

We will go through each of these subquestions as I discuss my results, but connected to my primary research questions and the themes reviewed through the groups were the following questions:

- What do the co-researchers know about trauma and its impacts?

- What type of practices do the co-researchers already do in their classroom to limit re-traumatization and increase resilience?

- What are the self-care practices of the teachers, and how do they manage secondary trauma?

- What practices can they develop together to promote change within their classrooms and schools?

- What effective systems or recommendations could the co-researchers create to help develop similar growth in other schools?

Slide 13

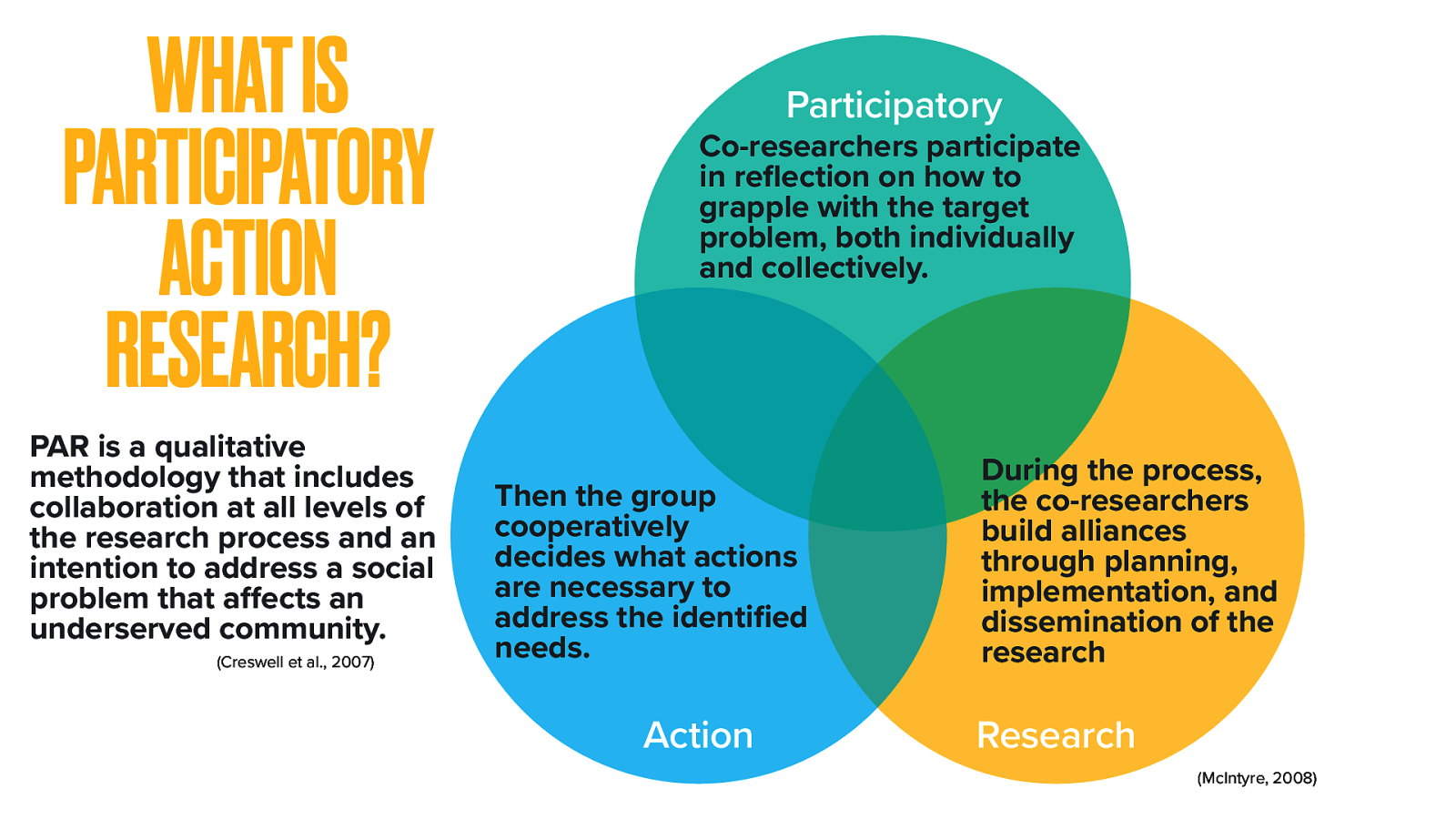

What is Participatory Action Research?

Before diving into the set up of this study, I also want to clarify what is participatory action research, or PAR. Creswell et al. (2017) describes that PAR is a qualitative methodology that includes collaboration at all levels of the research process and an intention to address a social problem that affects an underserved community.

It really has three parts to it…

- It is participatory: Co-researchers participate in reflection on how to grapple with the target problem, both individually and collectively.

- It is a research process: During the process, the co-researchers build alliances through planning, implementation, and dissemination of the research

- Action and creating change individually and collectively is a third core component: Then the group cooperatively decides what actions are necessary to address the identified needs.

(McIntyre, 2008)

Slide 14

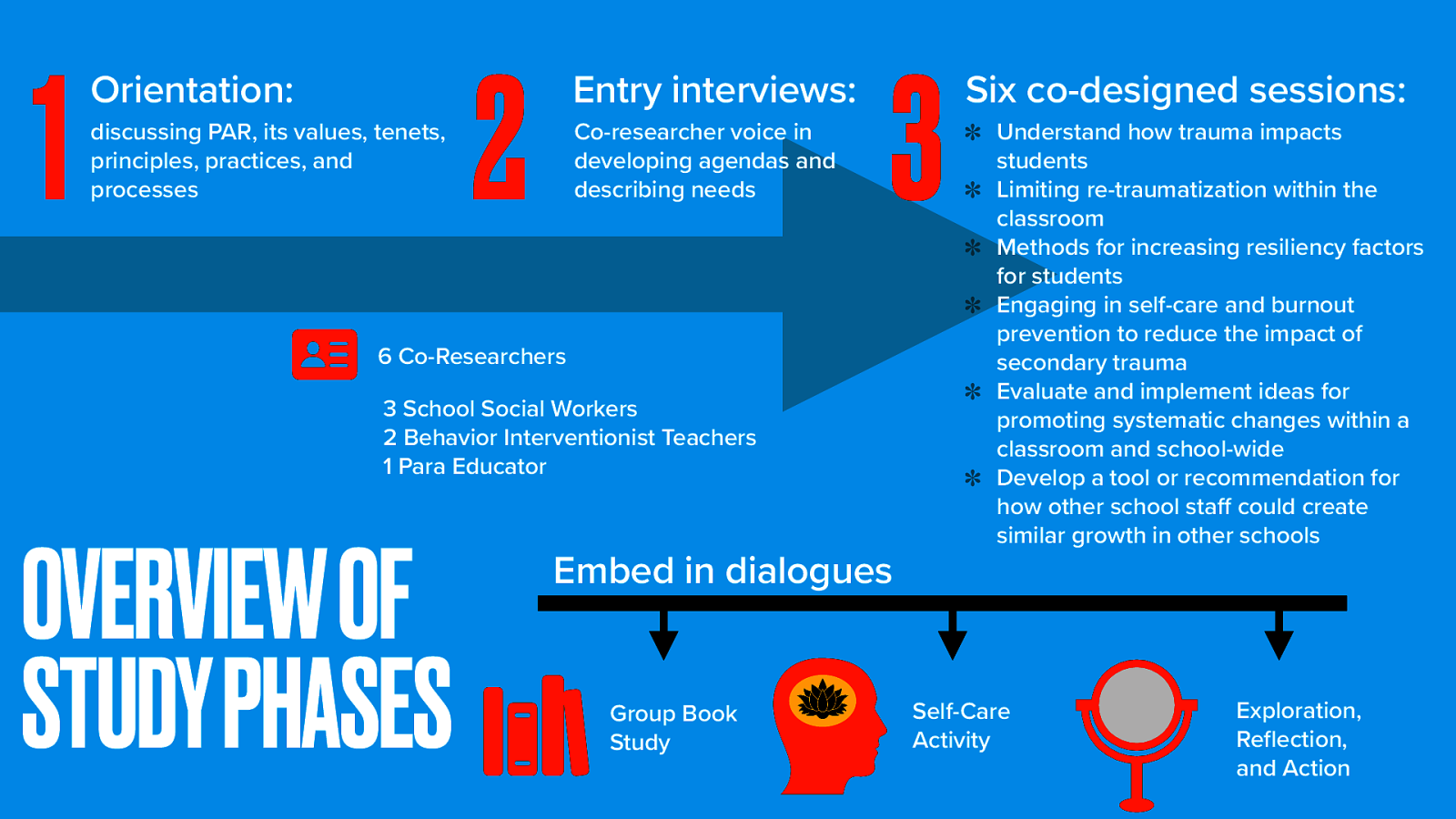

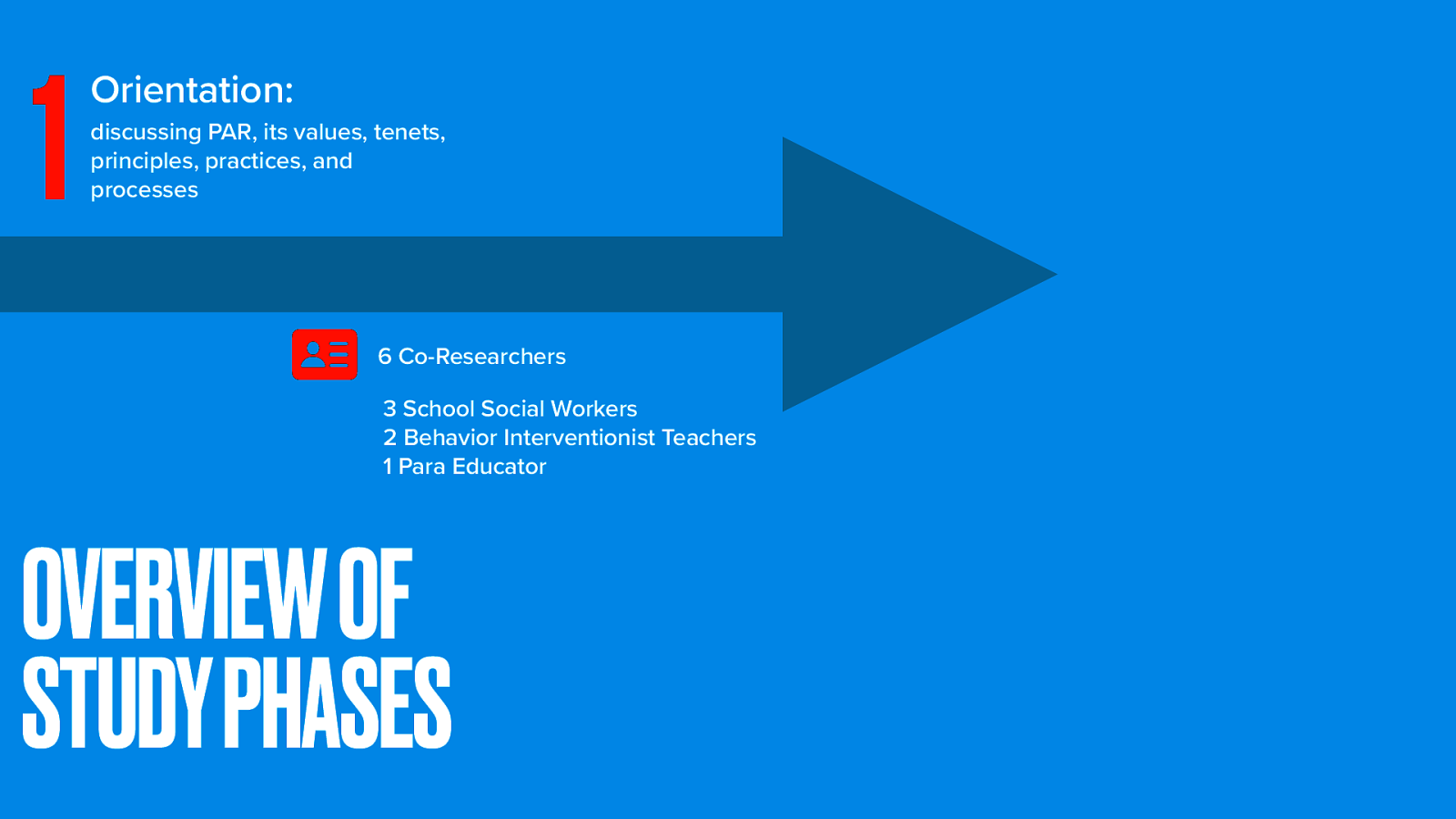

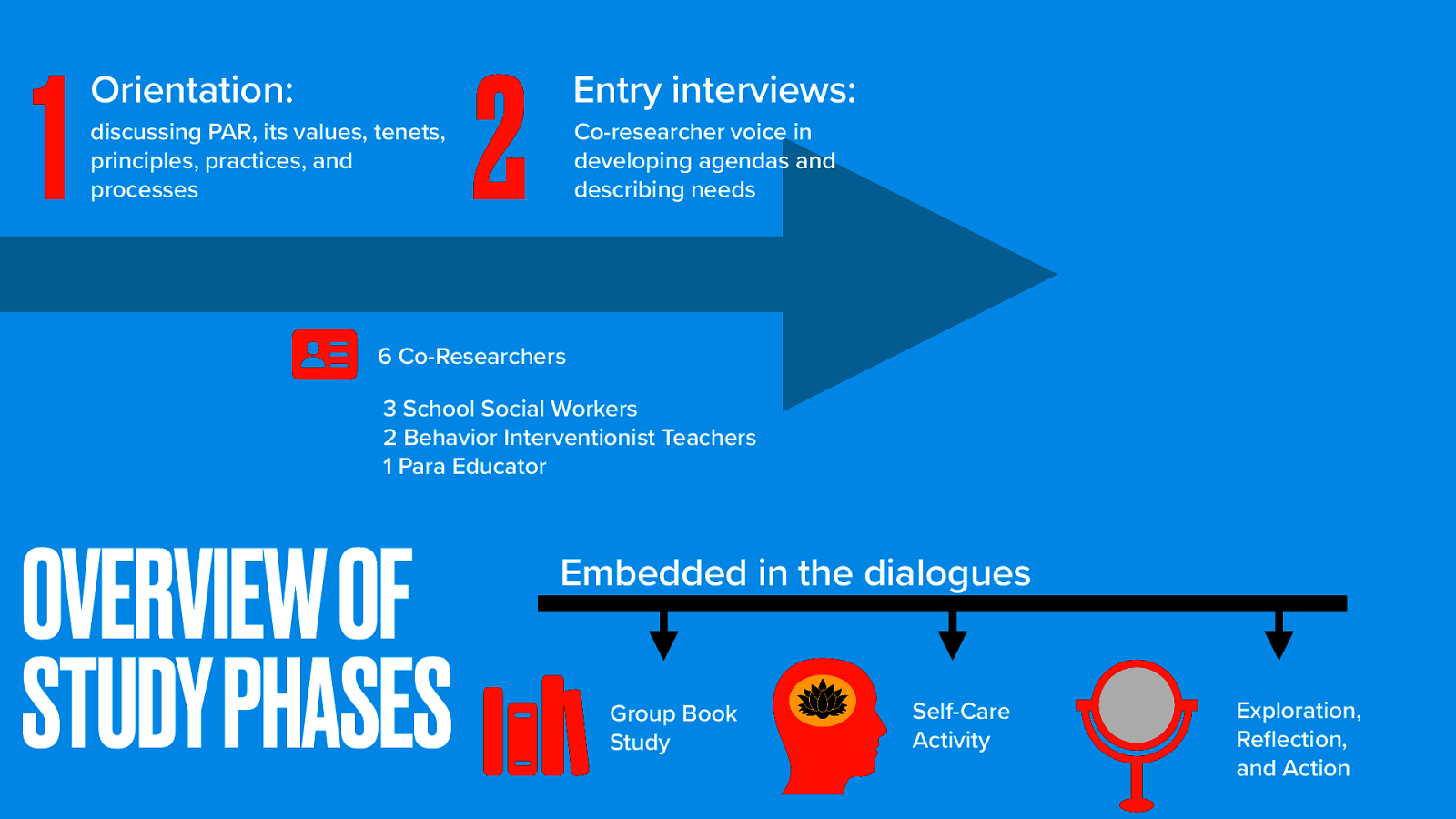

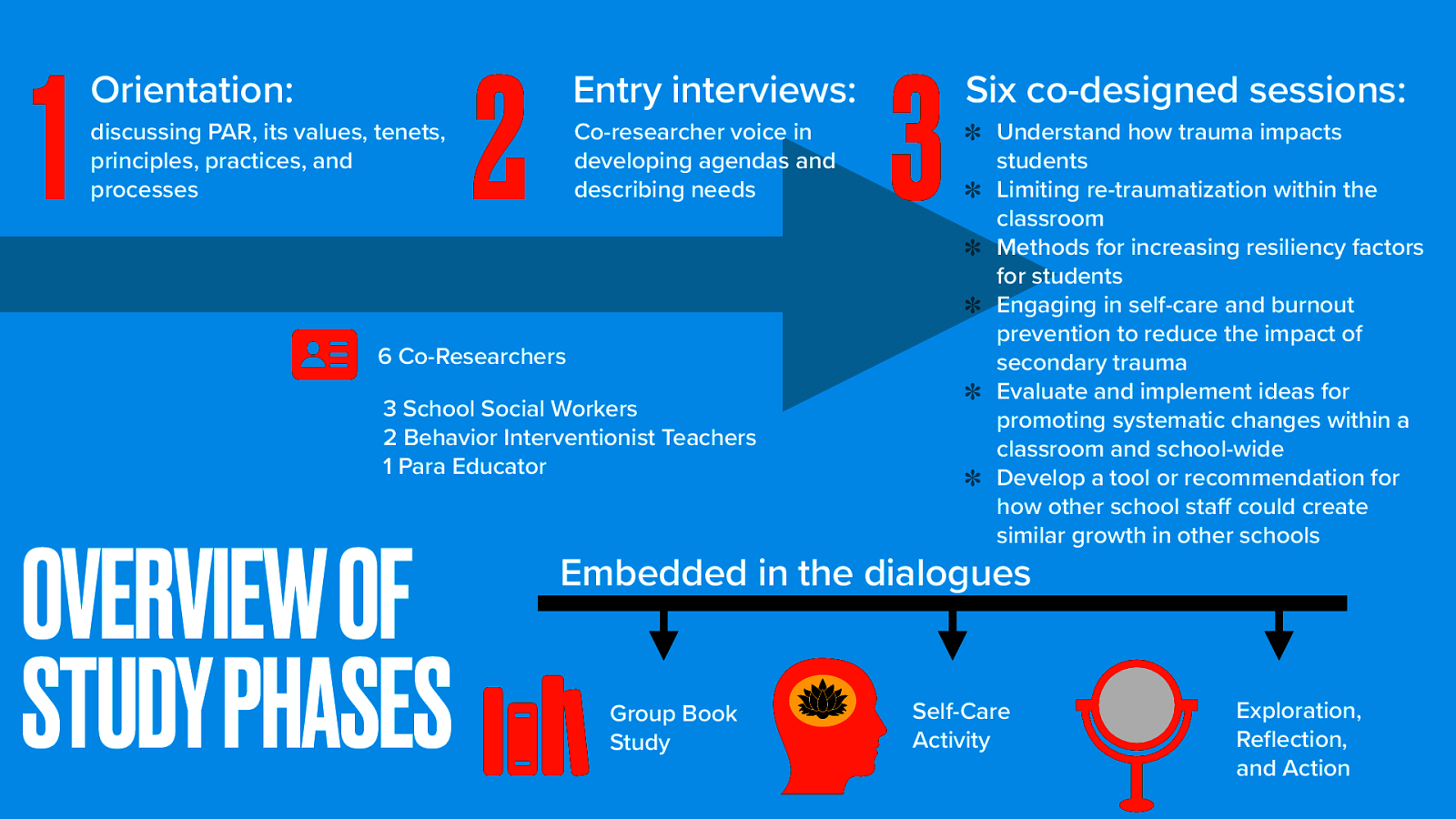

Overview of the Study Phases - Introduction to Study

This slide shows all of the parts of this study, the Trauma-Informed PLC. Sometimes you will also hear me refer to it as my PLC. We will be going through each of the these parts in turn to explain what I did before we discuss the results.

Slide 15

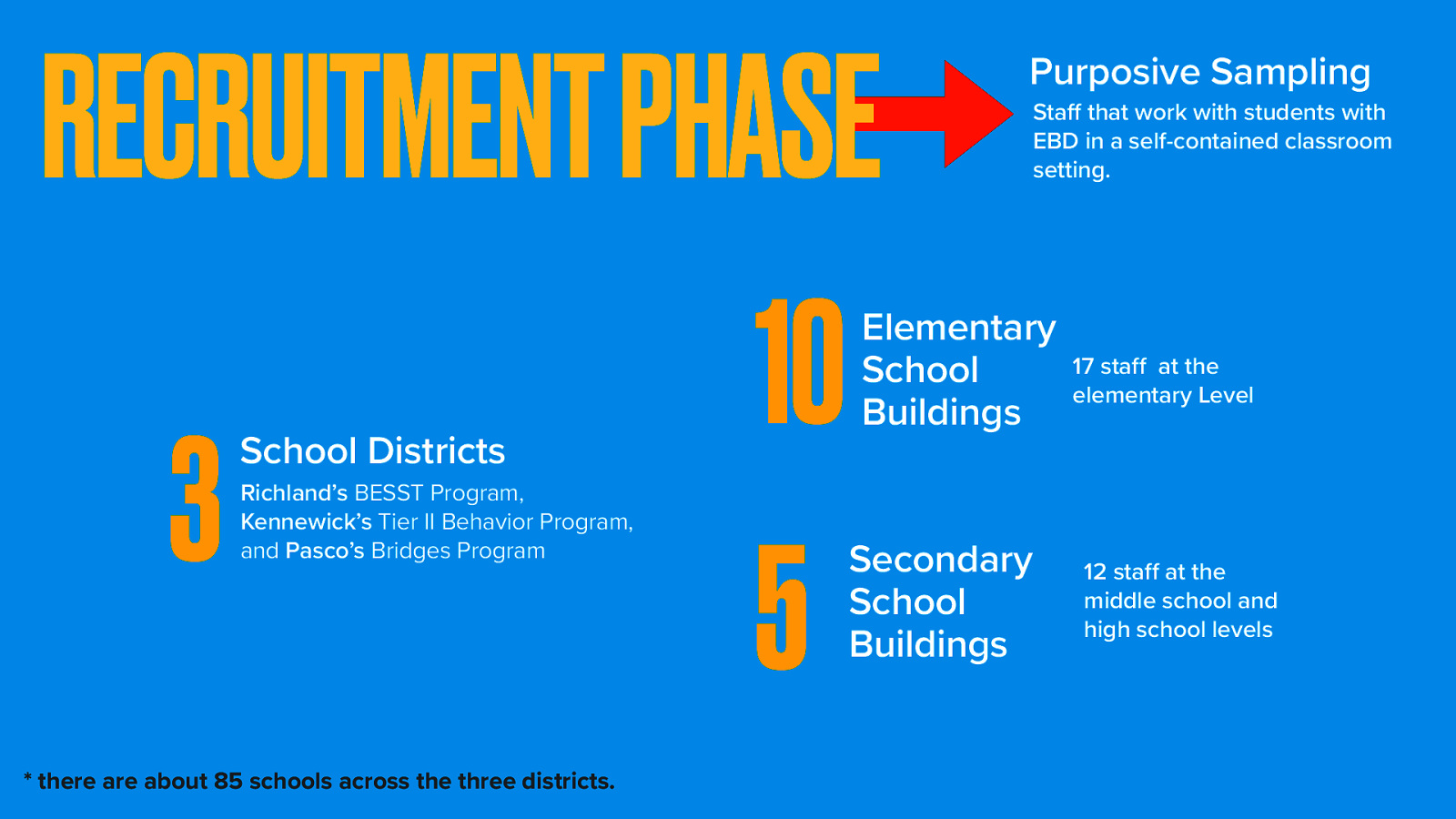

Recruitment Phase

The recruitment phase was the first stage of my research process. I used purposive sampling focused on staff that work with students with eBD in a self-contained special education classroom settings.

Specifically, in my local area, Tri-Cities Washington, there are three school district that are all very close. Each district has a program focused on supporting this group of students. Richland has the BESST Program, Kennewick has their Tier II Behavior Program, and my District Pasco has the Bridges Program.

I used my professional connections and each school district’s websites pages where they list staff names and emails to gather potential participants. I sent an email to district and building admin for each school that have one of these programs K-12. I also sent emails to any school staff that I could find working in these classrooms (e.g., special-education teachers, social workers, and para educators).

The number of actual possible participants was comparatively low. Of the about 85 schools across the three districts, there are only these programs at about 10 elementary buildings and 5 secondary buildings.

I also opportunistically was able to make an announcement at a behavior focused conference that I attended before my orientation meeting.

Slide 16

Orientation Meeting and Co-Researchers

The focus of my recruitment was to invite staff to attend an orientation session that was held via Zoom.

- I had 5 people people attend the orientation. I had a couple others reach out to me outside of the orientation with interest and I followed up with them via email. One participant from the orientation elected not to participate in the study due to time constraints, and one of the people who had emailed decided to participate in the study.

During the Orientation, I discussed what PAR is, it’s values, tenets, principles, and practices. We also discussed the study and reviewed the informed consent.

In total, after the orientation, we ended up with six total co-researchers (of which I am one). These were three school social workers, two behavior interventionist teachers (special education teachers), and a para educator.

Slide 17

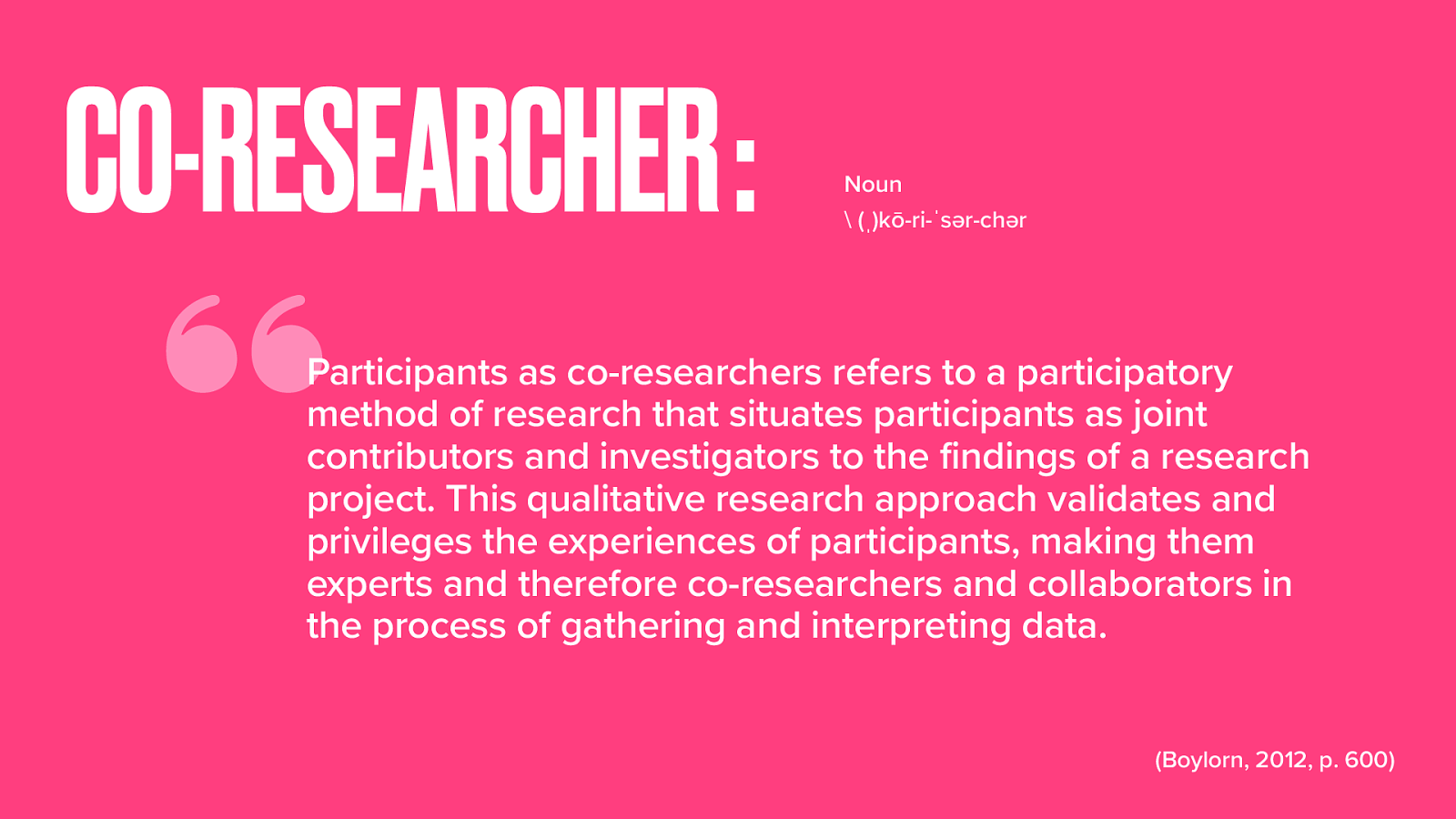

What is a Co-Researcher

Before we talk about each co-researcher, I want to define what a co-researcher is, as it is a fairly unique aspect of PAR.

In their encyclopedia entry for participants as co-researchers, Boylorn (2012) defines it as follows:

Participants as co-researchers refers to a participatory method of research that situates participants as joint contributors and investigators to the findings of a research project. This qualitative research approach validates and privileges the experiences of participants, making them experts and therefore co-researchers and collaborators in the process of gathering and interpreting data. (p. 600)

Slide 18

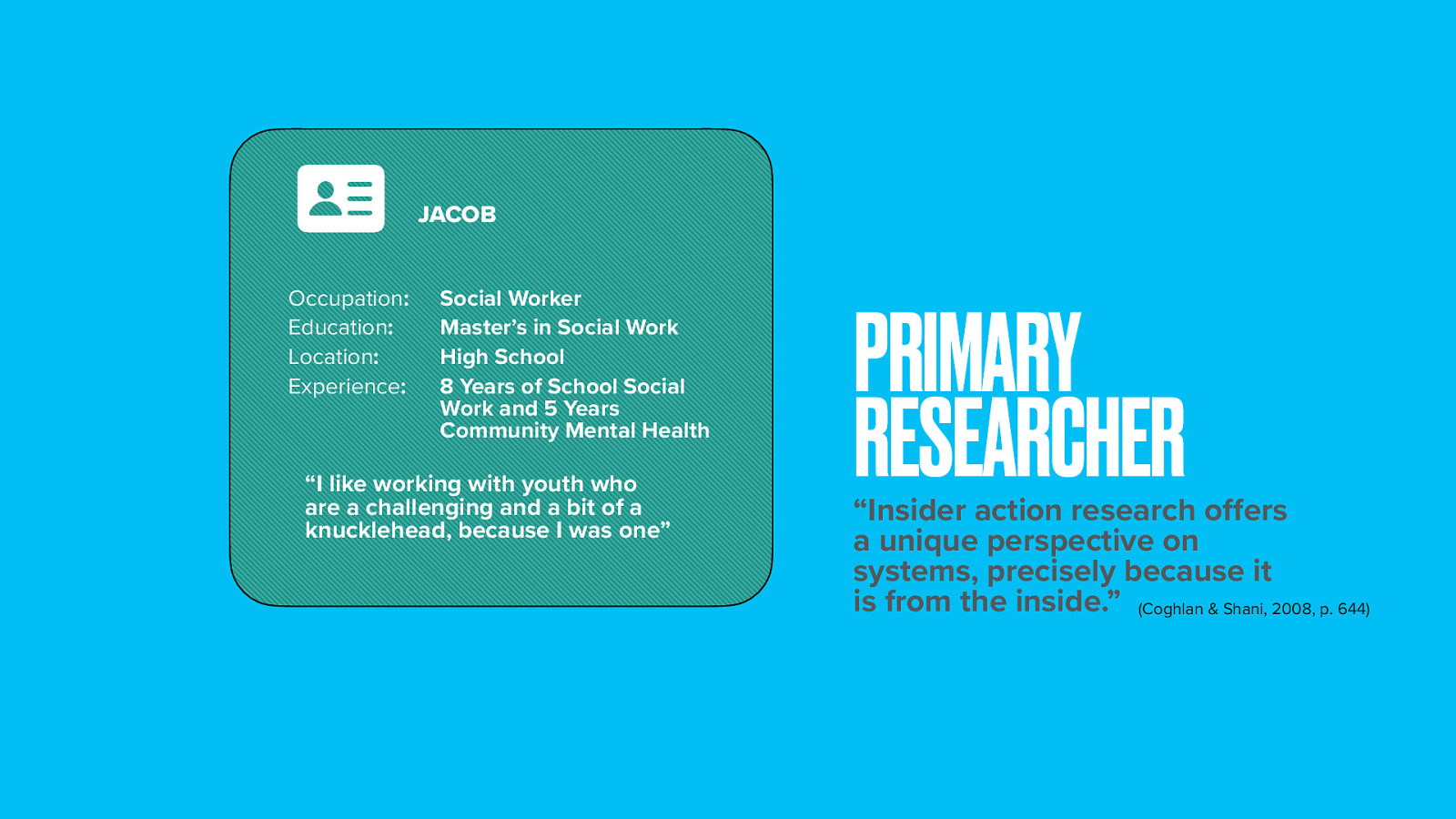

Primary Researcher

In this view of co-researchers, I am one of them. I will also refer to myself as the primary researcher as I have taken a leadership role in coordinating and facilitating the group using democratic methods. Data collection, analysis, and dissemniation were also completed by me.

Positionality is an important aspect of PAR and insider action research.

I connect and identify with having traumatic experiences. My father committed a triple homicide before I was born and was later executed by the state of Washington is one aspect that made a impact on my life and had an influence on my decision to become a social worker. Much of my high school career, I could have potentially been placed in a classroom like these serving students with EBD due to my behavior. I ended up going from a comprehensive high school to an alternative school to a private boarding school where I graduated and made changes in my life.

It was these experiences that made me want to go into social work and eventually work in a classroom serving students with EBD. I have 8 years working in a school based setting serving students with EBD and five years prior to working in community mental health. Like my other two social workers, I have my master’s in social work. I am also a licensed independent clinical social worker in WA. I work in a high school behavior program and am placed full time in that classroom. I support the therapeutic milieu of my classroom, as well as work individually in groups with my students in my program. I previously supported my program K-12 and also spent some time working in a special school run by a counseling agency focused on this same population of students. I am also an adjunct faculty for a university teaching social work classes.

My positionality also puts me as an insider researcher. Coghlan and Shani (2008) describe, “insider action research offers a unique perspective on systems, precisely because it is from the inside” (p. 644).

Slide 19

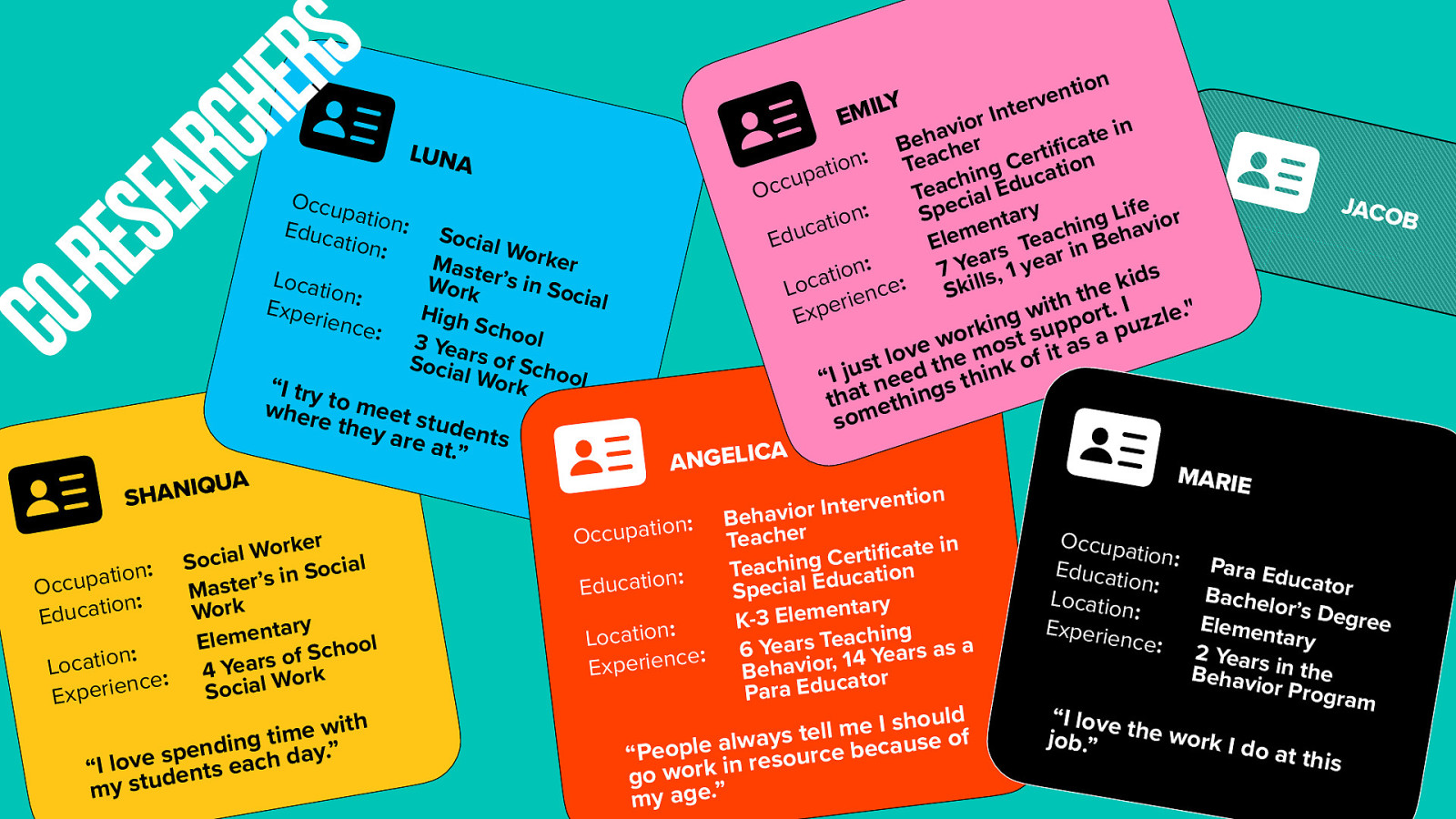

Co-Researchers

I asked each of my co-researchers to choose their own pseudonym for this study. The following are my co-researchers.

First I had two other social workers, Luna and Shaniqua. They respectively have 3 and 4 years of experience working in their programs. Luna works for a high school program that has two classrooms connected to it. Shaniqua works in an elementary setting that also has two classrooms with it. They are both in and out of their classrooms frequently and will do group and individual services with their students. When asked to talk about their roles and positions at their school Shaniqua said “I love spending time with my students each day” and talked about the 1:1 work she does with them. Luna explained that she tries “to meet students where they are at.”

Second, there were two special education teachers, Angelica and Emily. Both of them have their special education teaching credentials and are certificated teachers. Emily came from another district where she had 7 years of experience teaching students in a self-contained life-skills classroom (e.g., that program was focused more on students with more cognitive disabilities). This was her first year working in a program focused on students with behavioral disabilities. She described “I just love working with the kids that need the most support. I somethings think of it as a puzzle.” Angelica was the other teacher who participated in the group. She described “people always tell me I should go work in resource because of my age” as she explained that she waited until her kids were grown and out of the house to start her teaching program. She had six years of teaching in a behavior program and she was a para-educator for 14 years in similar programs. Both of the teachers work in elementary settings.

Finally, Marie told us that “I love the work I do at this job.” She was a para-educator in an elementary program and has been doing that for the last two years. She has a BA degree and is a current student working on her masters in social work.

Slide 20

Managing Power Dynamics with Co-Researchers

Power dynamics is an important topic when it comes to any part of PAR and study. This is especially true when the primary researcher has prior experience and connection with co-researchers. I have worked collaboratively with Angelica in the past and had shared students. In my role as an adjunct at the university I was one of Shaniqua and Luna’s teachers as they worked on their BA in social work before going on to their MSW program.

Grant et al (2008) have a chapter in a handbook for participatory research about relationships and power in PAR. I will use a few of their strategies to explain how I managed challenges related to power imbalances.

One strategy they describe is to “view research project as learning opportunity for all.” I was an active participant in the discussion, and took responsibility for creating the agenda and helping facilitate the discussion, I learned a lot as we went through the process. I will be sharing some examples of the new and novel ideas that were generated. The co-researchers all were vulnerable in sharing and growing their practice during the sessions. This emergent nature of this study is further evidence of this viewpoint.

Another strategy is to demystify the research process. The orientation session was focused almost exclusively on this.

A third strategy that is encouraged is to encourage involvement in all stages of the project, with increasing control. The individual entry interviews were how I developed all of the agendas of each meeting. Members would often bring up ideas and directions they wanted the conversation to go.

For example, during one of the sessions, Shaniqua made the comment “maybe we can talk about how do we tap out?” while we were talking about managing when we get frustrated working with a student or being triggered ourselves.

Slide 21

Overview of the Study Phases - Entry Interviews and Content Embedded in Dialogues

Before starting the actual group sessions, I conducted an entry interview with each of the co-researchers. During these sessions we talked about each of the themes we would talk about and brainstormed how we could learn about those topics.

During these entry interviews we also talked about what book we would plan to read together and potential self-care ideas to do during group.

Each session of the Trauma-Informed PLC had it’s own theme we focused on, but there were a few aspects that went across all of the dialogues. This included

- Group book study

- Self-care activity

- Exploration, reflection, and action

Slide 22

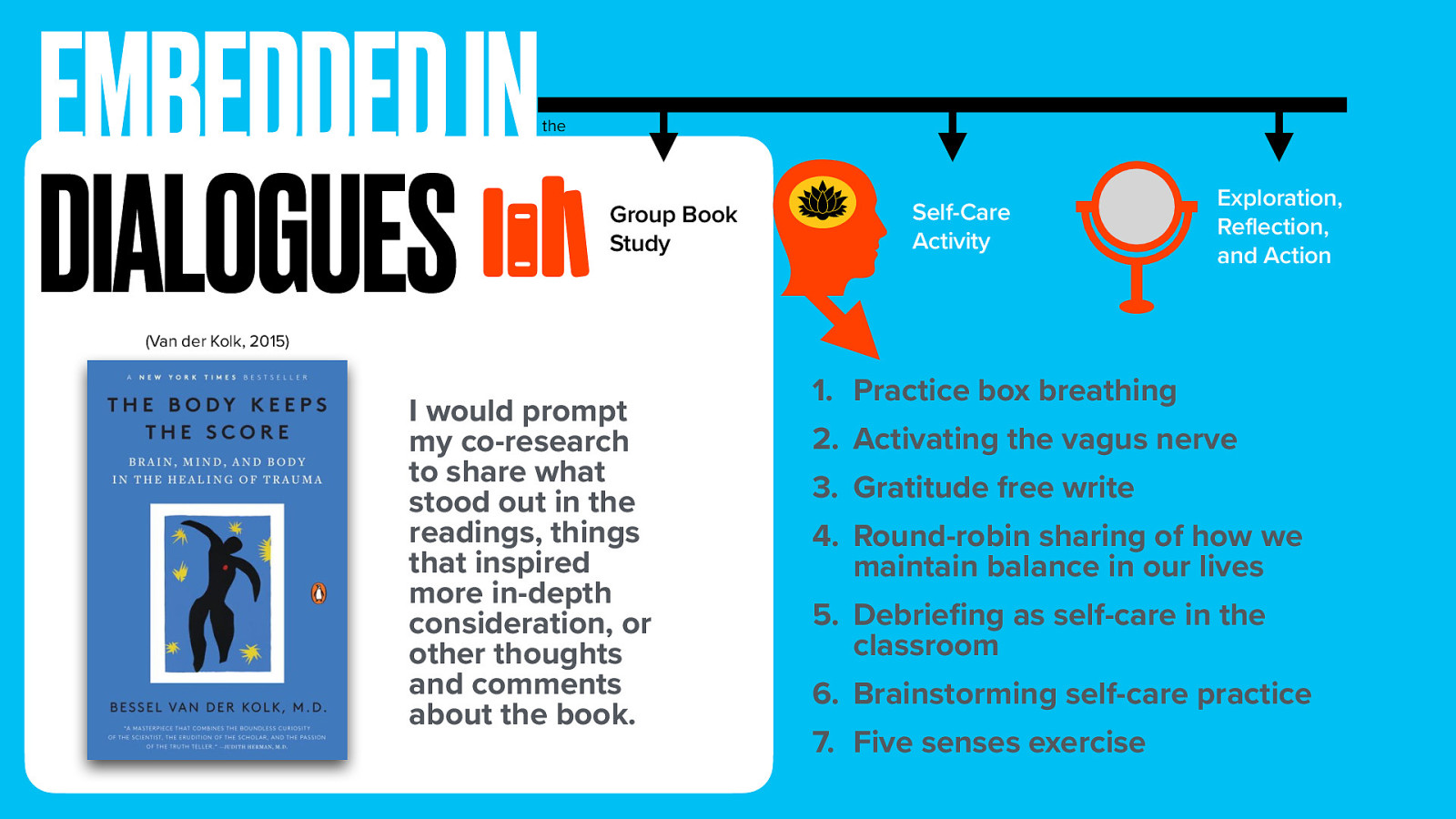

Embedded in the Dialogues

Group Book Study Self-Care Activity Exploration, Reflection, and Action (Van der Kolk, 2015) I would prompt my co-research to share what stood out in the readings, things that inspired more in-depth consideration, or other thoughts and comments about the book. fi EMBEDDED IN DIALOGUES the

- Practice box breathing 2. Activating the vagus nerve 3. Gratitude free write 4. Round-robin sharing of how we maintain balance in our lives 5. Debrie ng as self-care in the classroom 6. Brainstorming self-care practice 7. Five senses exercise

Slide 23

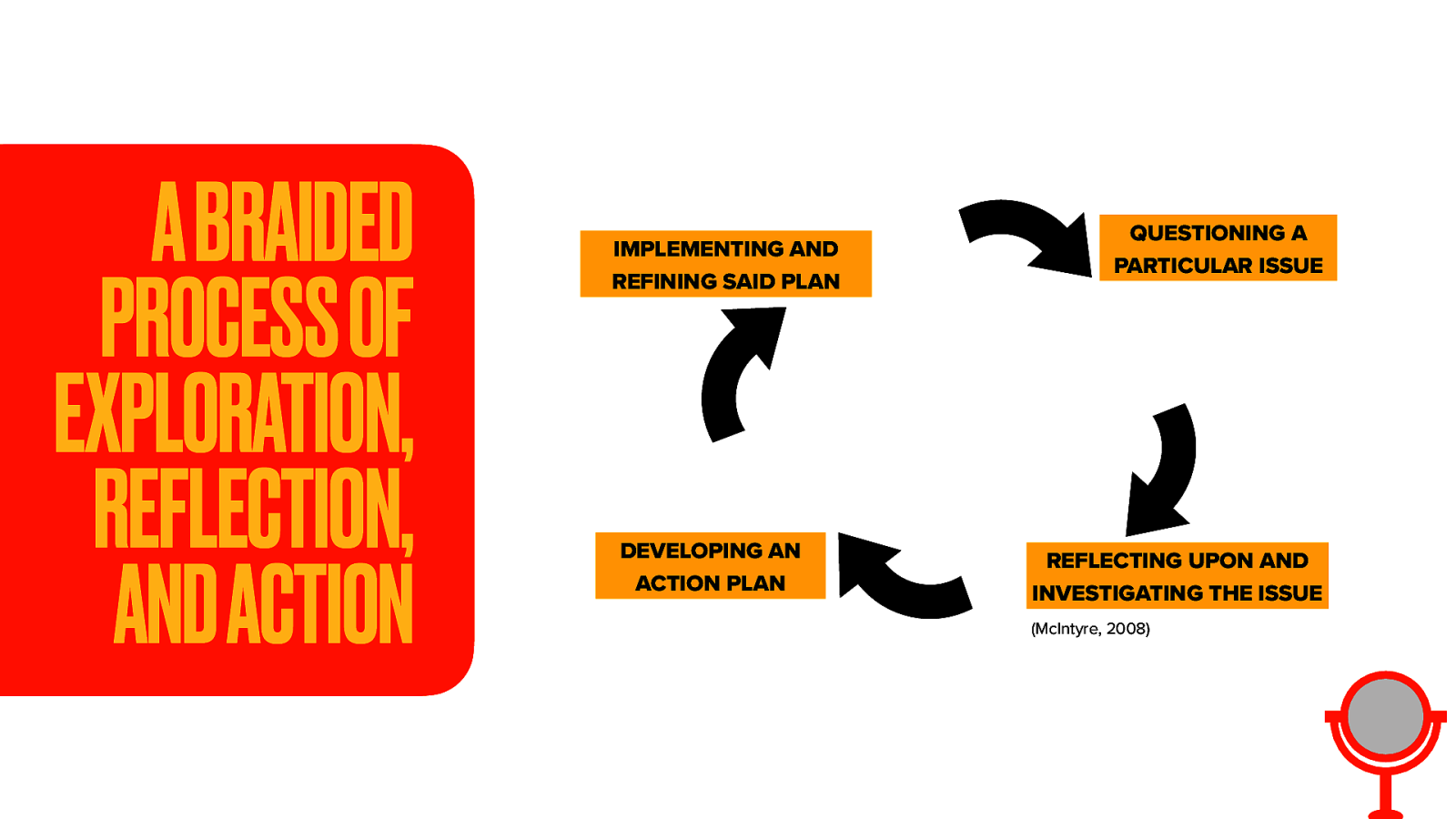

Braided process of exploration, reflection, and action

The braided process of exploration, reflection and action was embedded in each of the sessions McIntyre (2008) describes that this process includes a braided process of exploration, reflection, and action. This means it starts with

- questioning a particular issue

- reflecting upon and investigating the issue

- developing an action plan

- implementing and refining said plan

One powerful example of this happened when Angelica was sharing about her work with a young student she described as addicted to porn, and issues related to trauma, reporting to CPS, and communicating with families where there is secrecy.

- As a group, we questioned Angelica about the case, what had been doing.

- We spent time talking about it, other co-researchers shared thoughts about experiences from their practice.

- We came up with some action steps that Angelica could do to implement a plan with this scenario.

Slide 24

Overview of the Study Phases - Co-Designed Sessions

The bulk of the study took place in six co-designed sessions. I took the notes and ideas from my entry interviews and developed agenda’s each week for how we would talk about each of the following six themes:

- Understand how trauma impacts students

- Limiting re-traumatization within the classroom

- Methods for increasing resiliency factors for students

- Engaging in self-care and burnout prevention to reduce the impact of secondary trauma

- Evaluate and implement ideas for promoting systematic changes within a classroom and school-wide

- Develop a tool or recommendation for how other school staff could create similar growth in other schools

We will got through and talk about some of the work we did in each of these sessions.

Slide 25

Ideas and Content Used During Trauma-Informed PLC

During the entry interviews, there were many great ideas that came up. Many were included in the agenda for the session.

Not all of the ideas made it onto the agenda. I was pulling from each of the co-researchers ideas and compiling them. I knew that time would be limited for our sessions, and used my experience to pick out what seemed to be the best content to discuss each week.

Sometimes during the session, we would not make it through all of the material I had put on the agenda. For the purpose of our work together, it seemed best to follow the conversation where it went as led by the co-researchers. This meant that sometimes we came back to ideas the following week or we did not cover it. This attempt to draw out and seek emergent ideas seems to require to some degree that the agenda becomes the guideline and the co-researchers become the learning tool together.

Each of the themes for the sessions are incredibly deep. For the purpose of this study, we limited the number of sessions to six. I could imagine spending multiple sessions talking through each of the themes and there still be new learning and ideas to generate regarding that content.

Slide 26

Data Analysis

- Data Collected Included Session Notes

Agendas, notes that were taken during the session (both handwritten/typed), information from collaborative tools (e.g., Google Docs and Chat on Zoom), my reflections after the session, and information added after the session through the process of refining and processing the session notes for completeness

- Data Analysis Included

Processing notes and calling out themes and organizational structures as I found them. I added highlights and comments to organize information. Added information to a mind map to see it visually and assist in finding connections.

Slide 27

Foundational Aspects of the Trauma-Informed PLC

There were two foundation aspects that appeared through the sessions and seem important and different than most PLCs. These included:

- We functioned as a type of support group following a mutual aid model.

- We came together as an interdisciplinary working group.

Slide 28

Support Group using Mutual Aid

The literature around PLCs rarely focuses on the mutual aid aspects of a PLC. In examples when they do discuss it, it might be focused on resources and supplies.

Group members shared that they felt like our group was a support group in a more therapeutic sense. Shaniqua went right out and stated “it’s like a support group.” Angelica described feeling like “I don’t have a place that I feel comfortable” but how she felt comfortable with us in our group. Emily added that this group has been a positive outlet to address things and be around people with the “same mindset.”

When we took the ProQOL most all of the members scored a medium on either burnout or secondary traumatic stress (or both). The medium score mean that it is effecting you and your work to some extent and consistent with other staff in behavioral programs we have elevated levels of compassion fatigue.

Being a support group seems necessary. Some of the roles and functions we used in this support group included those described by Kurtz (2017)

- A facilitated the group

- Group engages in consulting, linking, and supporting

- Maintaining helping factors that includes promote feelings of similarity, acceptance, and support

Slide 29

Interdisciplinary Working Group

Interdisciplinary PLCs is another area that I was unable to find any research or implementaiton. There are many interdisciplinary teams in schools (IEP, Multitiered systems of support, my behavior team, etc) but not as a PLC. It seems to always be siloed

Having our group be made up of teachers, social workers and a para seemed very useful and helpful. There would be comments in the group such as:

“As a social worker, I…” or “As a teacher I…”

As well: Emily described, “I like hearing other people’s perspectives on things, just to hear what others do in the same field.” Later in talking about the social workers in the group, she explained it has been really “eye-opening” to hear the social worker side, “it’s just been fascinating learning more about trauma and those types of things.”

Choi and Pak (2006) provide a definition of interdisciplinary that I appreciate and aligns with my ideas.

“Interdisciplinary brings about the reciprocal interaction between (hence “inter”) disciplines, necessitating a blurring of disciplinary boundaries, in order to generate new common methodologies, perspectives, knowledge, or even new disciplines”

Slide 30

Learning Strategies: Cohesion Developing and Meaning Making

One of the takeaways that I came up with from the Trauma-Informed PLC was that finding opportunities to develop connections and be vulnerable was important. This often came out as we spent time making meaning of topics and practices.

There were many times that the group was vulnerable with each other and shared examples. During the second session, Angelica told us what we later referred to as the Backpack story. During a later session, Emily would comment that her telling the story made it so everybody could feel safe to share.

These sharing practical examples of practice was important to the learning and growth that happened and something that consistently happened..

- Developing working definitions (trauma, re-traumatization, resilience)

- Identifying aspects of concepts (various categories of trauma)

- Sharing personal challenges (individual and family mental health)

Slide 31

Learning Strategies: Idea Generation and Brainstorming

Another learning strategy that we frequently used as a part of PLC was idea generation and brainstorming.

One of the things that we used during several of the sessions used the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (2014) (see Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services) and the material they developed focused on social service agencies and implementing a trauma-informed care system in that setting. For example, in week 3, we reviewed 7 strategies they suggest for increasing resilience by counselors and we were able to translate those ideas into things that relate to kids and a K-12 school system.

Developing a list of ideas for implementation. We often just brainstormed ideas. One example is when we developed our definition of trauma. We developed a concise definition, but also came up with a string of related ideas that connect to trauma. We did this with a number of activities.

This brainstorming also allowed us to discover new and novel ideas. There was a lot we learned and ideas we heard that aren’t traditional talking points in training. For example, we had one member share about their “Bad Day Shirt” It became a whole different conversation, but it was an idea originally for self-care. Sometimes there were ideas that might also be considered too unprofessional, but could also be helpful for people. For example, Angelica described a mantra she has, when she feels like staff are being toxic towards her. She will tell herself “thank you for caring, fuck you for sharing”

Slide 32

Learning Strategies: Professional Socialization Through Sharing Process and Protocols

Another learning strategy that we used was sharing and reviewing protocols and processes.

- Sharing innovative or creative strategies (sitting in a box, exit candy)

- Specific ideas Generalized applications (transitioning students -> locks to social sorties, tours, meet and greets, etc)

- Miller (2010) Reviewing skills, values, professional identity, and attitudes that makeup professional socialization

We found a way to develop and socialize to our professional identity as social-emotional teachers.

Angelica described the population of her classroom, including students with both recent trauma and others with previous experience of trauma. She went on to express that all of her students “have got to learn their alphabet but to think that their brain is probably not capable to meet my expectations. It makes me feel like crap a lot of times when I think about that. I need to be focused on that as well as the academic piece.” Emily clarified, “we are social-emotional teachers. That’s my role. It is academics too, but that’s not the most important part of my job.”

Examples of each area: Skills: (transitions) Values: (safe learning environment) Professional identities: Teacher Couselor Attitudes: downplaying comments

Slide 33

What do the co-researchers know about trauma and its impacts?

To clarify how we made clear and worthwhile change, I want to review each of the research questions we asked:

The explicit focus on trauma and its impact was the theme for the first session, but it carried through all of the other sessions. As we processed our practices and work with students, we contextualized these discussions using the student’s experiences and stories.

- We framed our discussion regarding trauma and its impacts considering the ten ACEs first described by Felitti et al. (1998) and using the list of types of trauma from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (n.d.).

- As a PLC, we co-defined trauma as a topic and explored the impacts that we have seen from our students and our personal lives.

- We explored our experiences working with students or clients with diverse traumatic histories.

- We generated ideas on how somebody might experience the types of traumas and how it appeared to impact them in their lives at home and school.

Slide 34

What type of practices do the co-researchers already do in their classroom to limit re-traumatization and increase resilience?

the second research question was ^^

The selected themes of the second and third sessions were limiting re-traumatization and increasing resiliency.

- The co-researchers frequently shared examples of their engagement with students and practices used in their classrooms.

- We made meaning through the development of working definitions of re-traumatization and resilience.

- We developed a framework for understanding resilience that relates it to internal versus external resiliency factors.

- We built on the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (2014), and the strategies recommended to build resilience by counselors as we drafted examples of how they could be adapted to a school setting.

Slide 35

What are the self-care practices of the teachers, and how do they manage secondary trauma?

The third research question was ^^

Reducing secondary trauma and centering on self-care practices was the theme of the fourth dialog.

- Each session, the co-researchers engaged in a self-care practice to develop our skills and repertoire in self-care practices.

- We considered our personal experience with secondary trauma using the ProQOL (Hudnall Stamm, 2010).

- We used idea generation to reflect on new and novel ideas for self-care practices.

- The structure of the group, acting as a type of support group using mutual aid practices, offered support in managing compassion fatigue.

Slide 36

What practices can they develop together to promote change within their classrooms and schools?

The fourth research question was ^^

The specific theme for session five was focused on ideas that could promote change within our classrooms and schools We followed the model for participatory action research, which included …

- The co-researchers used the group as a space to discuss individual practices and work within our classrooms and schools.

- This process led to a type of socialization, developing practice improvements.

- We would reflect on these practices and share their application.

- Often there would be plans made for making changes in our settings and following up about those plans or implementation afterward to continue refining our practice.

Slide 37

What effective systems or recommendations could the co-researchers create to help develop similar growth in other schools?

The fifth and final research question was ^^

Session six was structured to examine if the format of a Trauma-Informed Care PLC should be shared as a way of learning about trauma-informed care practices.

- We discussed the need for a practical cookbook-style guide that school personnel could use to develop their own Trauma-Informed PLC.

- The group members shared their desires to continue having a space to meet with and talk with fellow peers and people who work in their specific field of practice to continue to develop and improve their practice skills.

- They all reported being interested in continuing the work we began in the Trauma-Informed Care PLC the following school year.

- We developed specific recommendations for how schools can prevent secondary traumatization by structuring our proposals based on Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (2014) list of recommendations for behavioral health centers, adapting the strategies to what would make sense in a school-based setting.

Slide 38

Limitations

We also need to consider the limitations of the study.

- Study was exploratory (Meant to provide insight and a potential model)

- The group composition (Great co-researchers, but might be biased. )

- Not focused on external measures or processes (would benefit from having how much change or tools like Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care Scale)

- Potential for ambiguity and misunderstanding (storytelling and self-report)

- Does not evaluate implementation or programs

Slide 39

Managing with a Broken Wand

During one of the sessions, Shaniqua was talking about how we are always called in to “fix” students. First, this isn’t the perspective any of our group take, and second she described feeling “it is like my wand is broken.”

The co-researchers felt their work during the dialogs was beneficial. They generally seemed to be encouraged about the process. Luna said, “I got a little bit of my, we are going to change the world back”

This work is hard, and a support group like this seems really needed. Marie described how she felt before “I think I’m just burnt out from life. I think that it is bleeding into work.”

Angelica summed it up “I mean, and I know that I could, I could call one of you guys and say, Hey, this is happening. I need to talk about this. I mean, I would feel like I could do that at this point and say, What do you guys think?”

This type of system can be beneficial for staff working with students with EBD to learn how to manage with a broken wand.

Slide 40

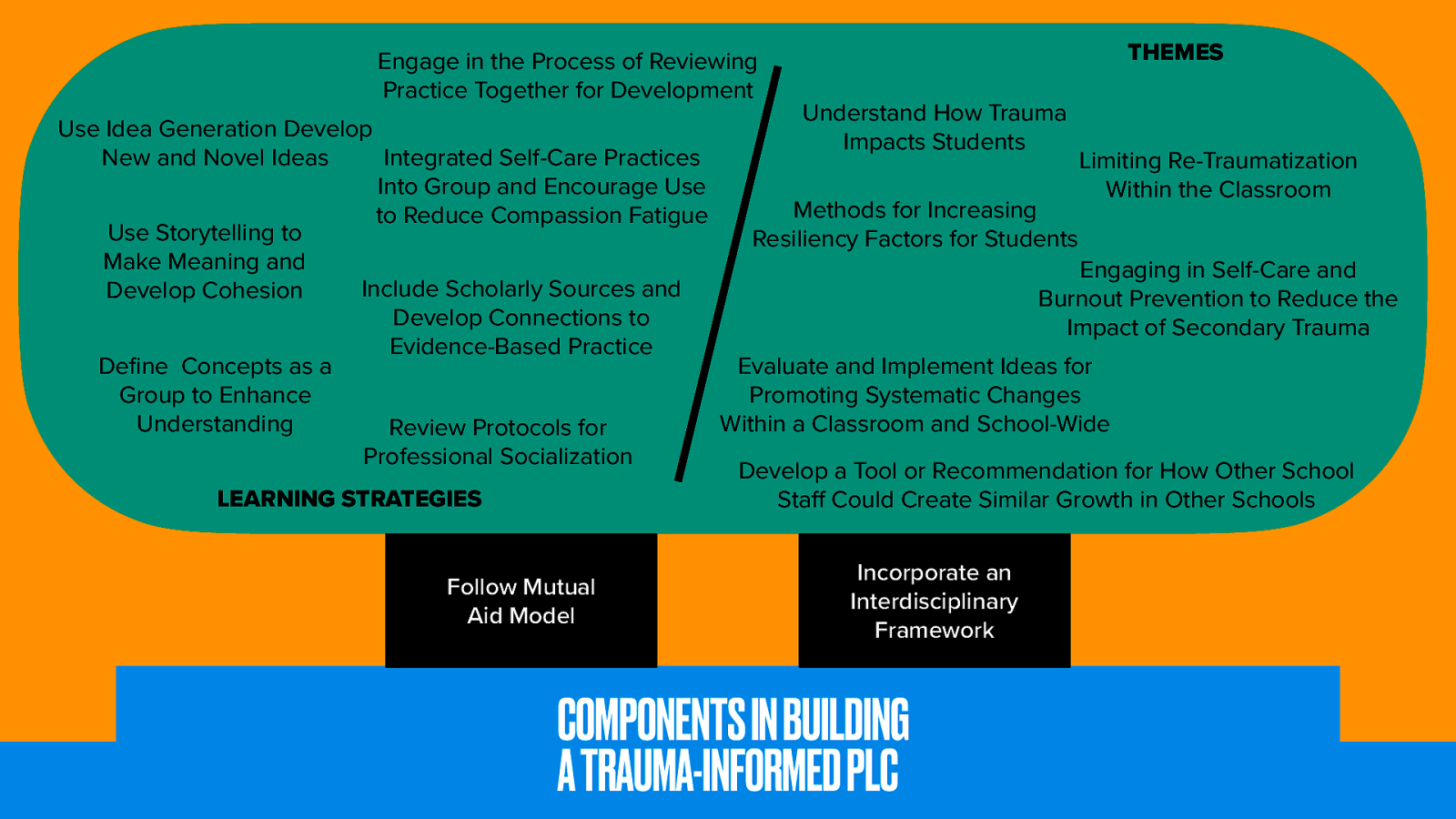

Components of building a trauma-informed PLC

The following graphic describes all of these components that I have gone through and reviewed. They include the foundations of:

- Following a mutual aid model

- Incorporate an Interdisciplinary Framework

The themes of

- Understand How Trauma Impacts Students

- Limiting Re-Traumatization Within the Classroom

- Methods for Increasing Resiliency Factors for Students

- Engaging in Self-Care and Burnout Prevention to Reduce the Impact of Secondary Trauma

- Evaluate and Implement Ideas for Promoting Systematic Changes Within a Classroom and School-Wide

- Develop a Tool or Recommendation for How Other School Staff Could Create Similar Growth in Other Schools

And the learning strategies of

- Engage in the Process of Reviewing Practice Together for Development

- Use Idea Generation to Develop New and Novel Ideas

- Integrated Self-Care Practices Into Groups and Encourage Use to Reduce Compassion Fatigue

- Use Storytelling to Make Meaning and Develop Cohesion

- Include Scholarly Sources and Develop Connections to Evidence-Based Practice

- Define Concepts as a Group to Enhance Understanding

- Review Protocols for Professional Socialization

Slide 41

References

Bethell, C. D., Davis, M. B., Gombojav, N., Stumbo, S., & Powers, K. (2017). Issue brief: A national and across state profile on adverse childhood experiences among children and possibilities to heal and thrive. pages. http://www.changeimpact.net/uploads/1/0/2/1/102192352/ti.aces_issue_brief-_oct_2017.pdf

Bethell, C. D., Gombojav, N., Solloway, M., & Wissow, L. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences, resilience and mindfulness-based approaches: Common denominator issues for children with emotional, mental, or behavioral problems. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25(2), 139-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2015.12.001

Bettini, E., Cumming, M. M., O’Brien, K. M., Brunsting, N. C., Ragunathan, M., Sutton, R., & Chopra, A. (2019). Predicting special educators’ intent to continue teaching students with emotional or behavioral disorders in self-contained settings. Exceptional Children, 86(2), 209-228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402919873556

Boylorn, R. M. (2012). Participants as Co-Researchers. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods (pp. 600-601). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909.n310

Bridget, V. D., Tara, C. R., Erin, D., & Cody, H. (2016). Addressing Disproportionality in Special Education Using a Universal Screening Approach. The Journal of Negro Education, 85(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.85.1.0059

Cavanaugh, B. (2016). Trauma-informed classrooms and schools. Beyond Behavior, 25(2), 41-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/107429561602500206

Slide 42

References Continued

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services: treatment improvement protocol (TIP) series 57. No. (SMA) 13-4801. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 342 pages. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK207201.pdf

Choi, B. C. K., & Pak, A. W. P. (2006). Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clinical and Investigative Medicine. Medecine Clinique Et Experimentale, 29(6), 351-364.

Coghlan, D., & Shani, A. B. R. (2008). Chapter 45 - Insider action research: The dynamics of developing new capabilities. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Action Research (2nd Eds. ed., pp. 643-655). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607934.n56

Creswell, J. W., Hanson, W. E., Clark Plano, V. L., & Morales, A. (2007). Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(2), 236-264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006287390

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Grant, J., Nelson, G., & Mitchell, T. (2008). Chapter 41 - Negotiating the challenges of participatory action research: Relationships, power, participation, change and credibility. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), SAGE Research Methods The SAGE handbook of action research (2nd Eds ed., pp. 588-601). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607934

Hoffman, S., Palladino, J. M., & Barnett, J. (2007). Compassion fatigue as a theoretical framework to help understand burnout among special education teachers. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 2(1), 15-22.

Hord, S. M. (1997). Professional learning communities: Communities of continuous inquiry and improvement., 72 pages. https://sedl.org/pubs/catalog/items/cha34.html

Hudnall Stamm, B. (2010). The Concise ProQOL Manual (2nd ed.)., 74 pages. https://proqol.org/proqol-manual

Slide 43

References Continued

Johnson, A. (2018). Supporting teachers through social and emotional learning. Success in High-Need Schools Journals, 14(1), 26-29.

Kan, K., Gupta, R., Davis, M. M., Heard-Garris, N., & Garfield, C. (2020). Adverse experiences and special health care needs among children. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24(5), 552-560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-020-02874-x

Kurtz, L. F. (2017). Chapter 09 - Support and self-help groups. In C. D. Garvin, L. M. Gutierrez, & M. J. Galinsky (Eds.), Handbook of Social Work with Groups (pp. 155-170). The Guilford Press.

Leonard, A. M., & Woodland, R. H. (2022). Anti-racism is not an initiative: How professional learning communities may advance equity and social-emotional learning in schools. Theory Into Practice, 61(2), 212-223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2022.2036058

MacDonald, C. (2012). Understanding participatory action research: A qualitative research methodology option. The Canadian Journal of Action Research, 13(2), 34-50. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v13i2.37

McIntyre, A. (2008). Participatory Action Research. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483385679

Mertens, D. M. (2009). Transformative research and evaluation. The Guilford Press. https://ciis.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=262493&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Montuori, A., & Donnelly, G. (2017). Transformative leadership. In J. Neal (Ed.), Handbook of personal and organizational transformation (pp. 1-33). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29587-9_59-1

Nelson, C. M. (2014). Chapter 5 - Students with learning and behavioral disabilities and the school-to-prison pipeline: How we got here, and what we might do about It. In Advances in Learning and Behavioral Disabilities: Special Education Past, Present, and Future: Perspectives from the Field (pp. 89-115). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/s0735-004x20140000027007

Slide 44

References Continued

Perfect, M. M., Turley, M. R., Carlson, J. S., Yohanna, J., & Saint Gilles, M. P. (2016). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015. School Mental Health, 8(1), 7-43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9175-2

Stroh, D. P. (2015). Systems thinking For social change: A practical guide to solving complex problems, avoiding unintended consequences, and achieving lasting results. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Tefera, A. A., & Fischman, G. E. (2020). How and why context matters in the study of racial disproportionality in special education: Toward a critical disability education policy approach. Equity & Excellence in Education, 53(4), 433-448. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2020.1791284

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.). Trauma types. https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types

Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Department of Health & Human Services. The United States, pages. https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4884.pdf

Trout, A. L., Epstein, M. H., Nelson, R., Synhorst, L., & Duppong Hurley, K. (2006). Profiles of children served in early intervention programs for behavioral disorders. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 26(4), 206-218. https://doi.org/10.1177/02711214060260040201

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma.

Webster-Wright, A. (2009). Reframing professional development through understanding authentic professional learning. Review of Educational Research, 79(2), 702-739. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308330970

Ziaian-Ghafari, N., & Berg, D. H. (2019). Compassion fatigue: The experiences of teachers working with students with exceptionalities. Exceptionality Education International, 29(1). https://doi.org/10.5206/eei.v29i1.7778