Doctoral Dissertation Oral Defense by Jacob Campbell

A presentation at Heritage University in March 2023 by Jacob Campbell and is tagged with PhD. Dissertation Defense, California Institute of Integral Studies

Description

This presentation is the slides used during my doctoral defense at the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) in the Transformative Studies Department. My finalized and published dissertation can be found published under open access. See if on ProQuest.

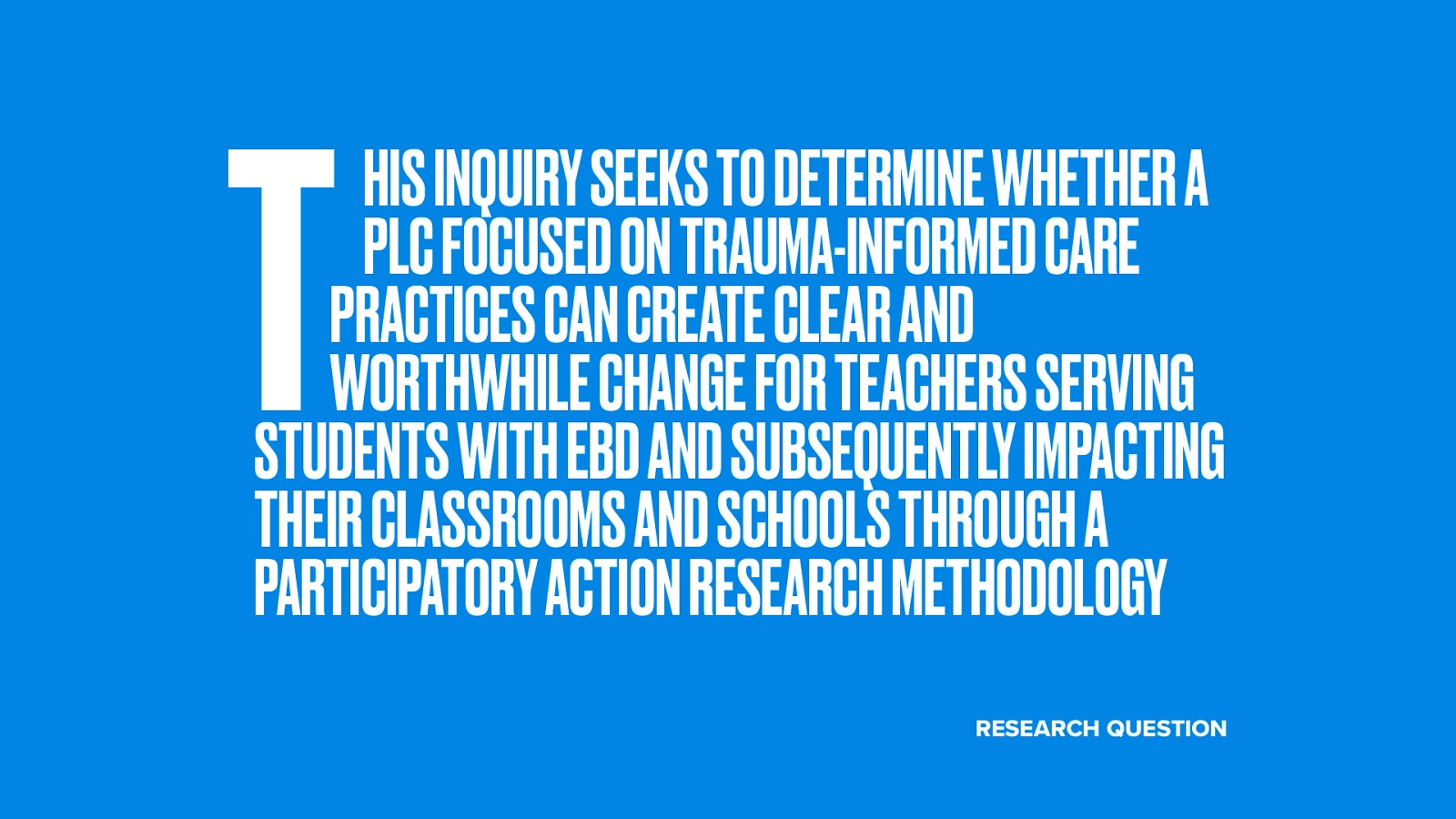

Title: A Professional Learning Community for Developing Trauma-Informed Practices Using Participatory Action Methods: Transforming School Culture for Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disabilities

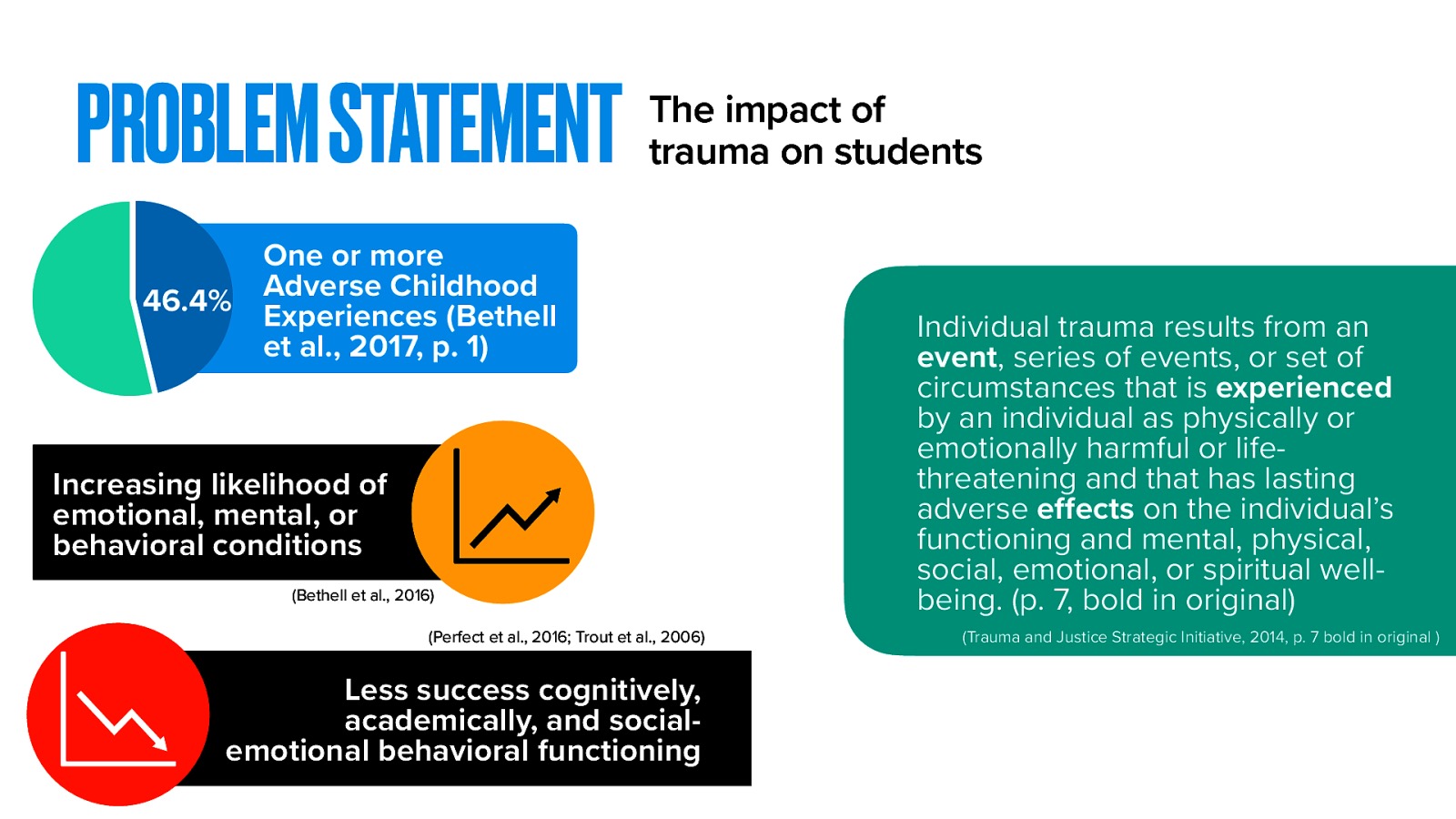

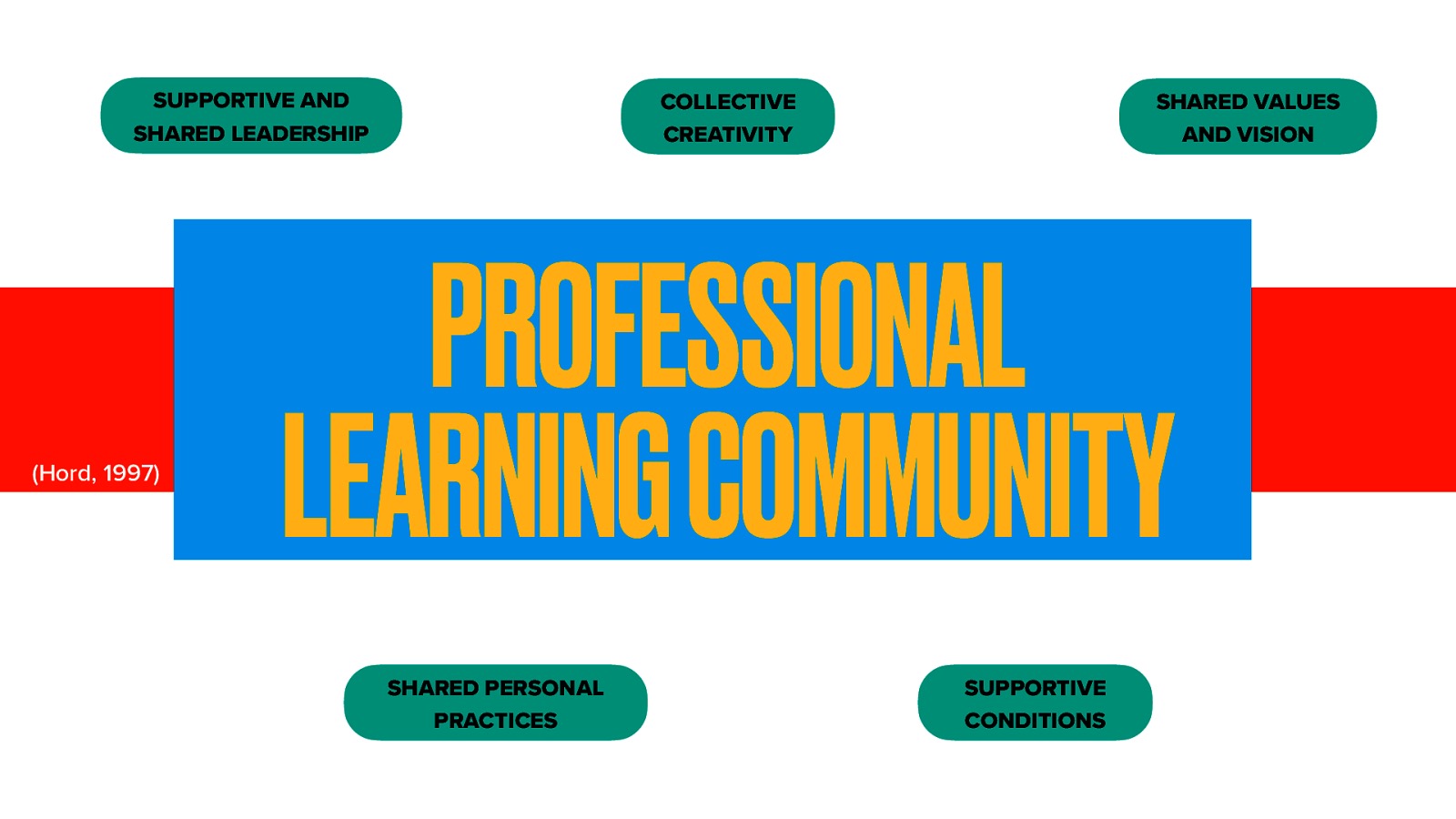

Abstract: Students with emotional and behavioral disabilities (EBD) endure adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and other traumatic experiences at higher rates than their non-disabled peers. Staff who work with these students can experience compassion fatigue, contributing to staff attrition and burnout. Trauma-informed care practices show promise in supporting staff and students. The primary method generally used for teaching about these practices is workshop-style training. The professional learning community (PLC) presents a learning model directed by its team but is currently centered around teachers and academic curriculum discourse.

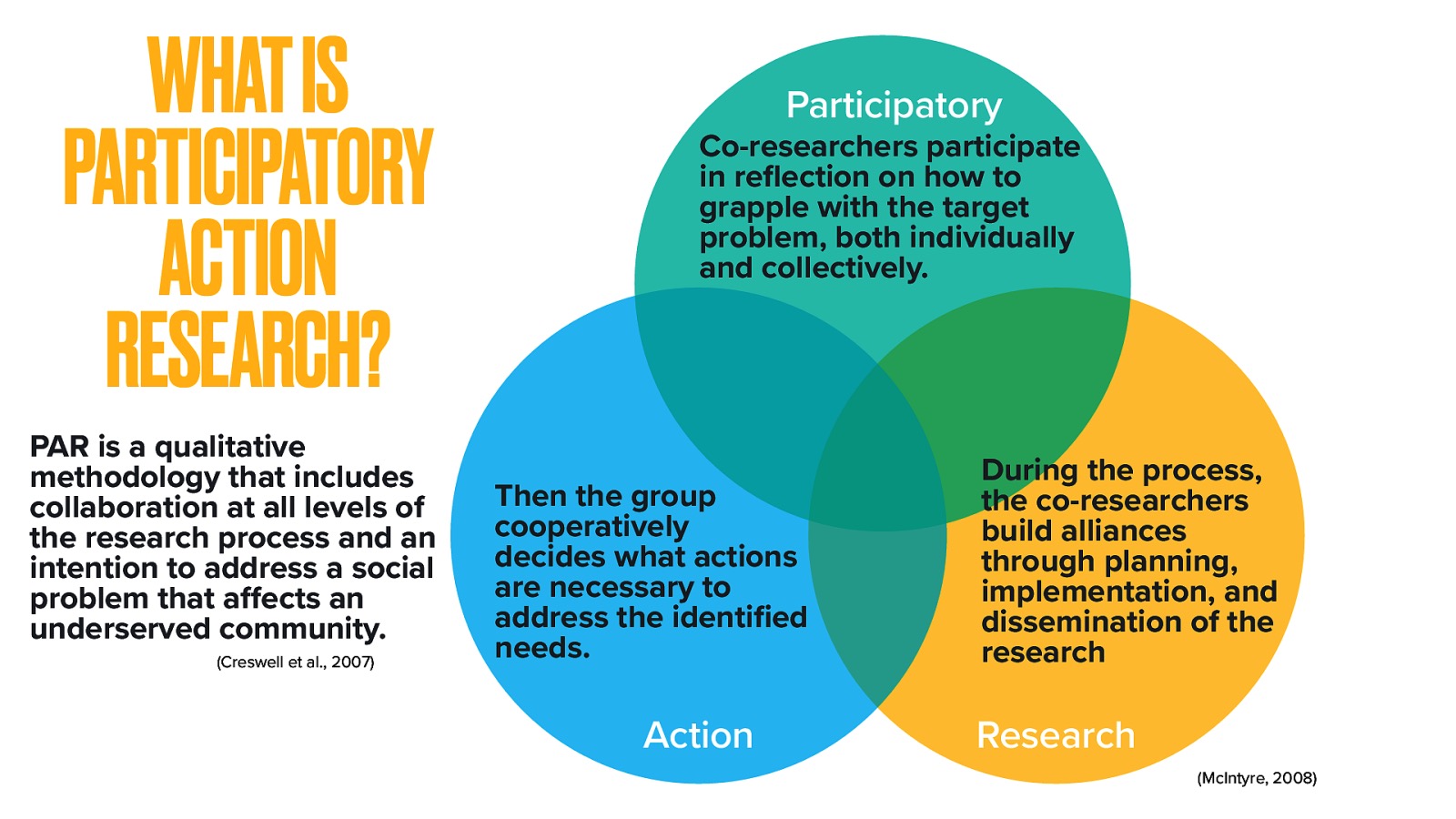

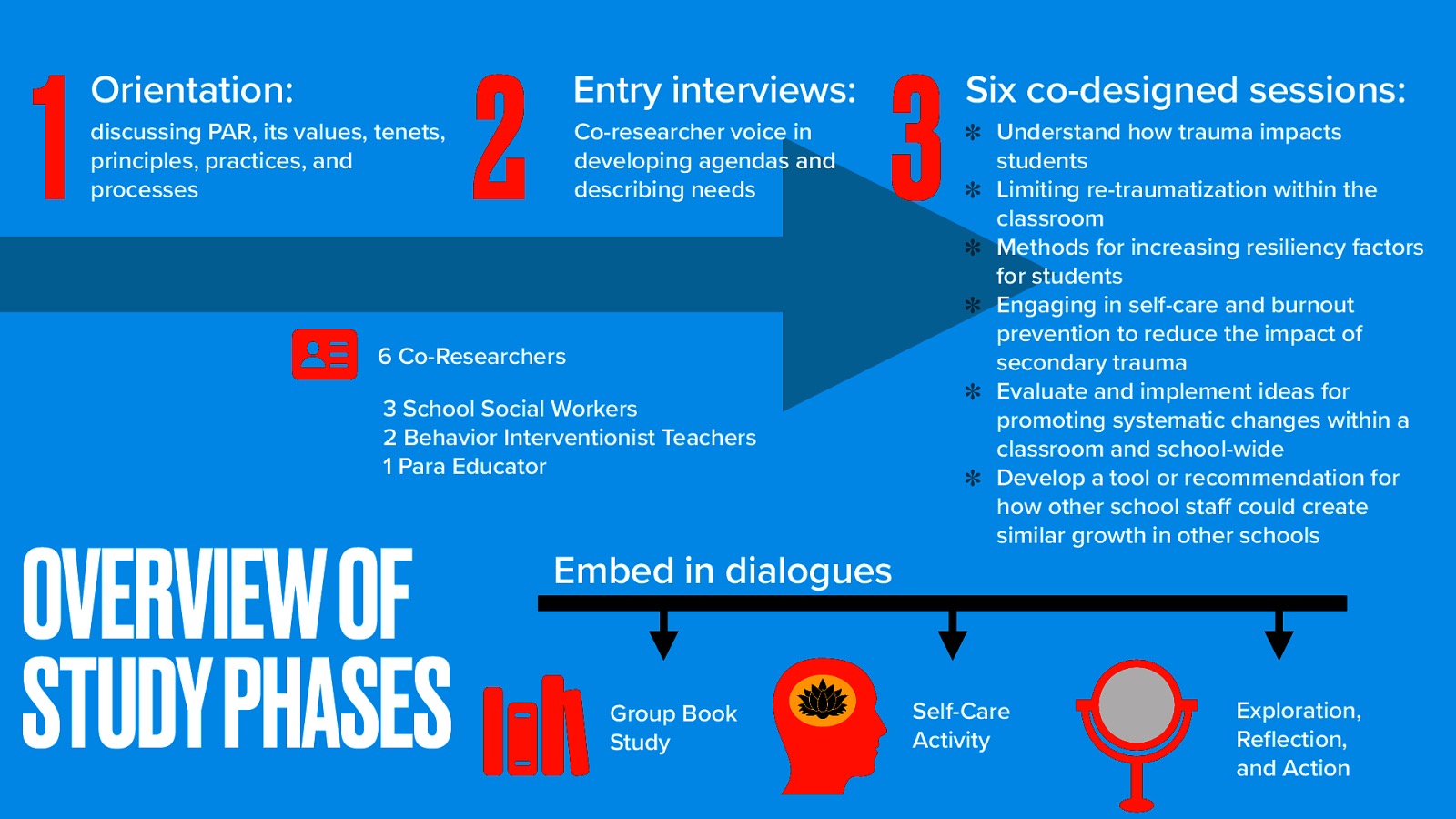

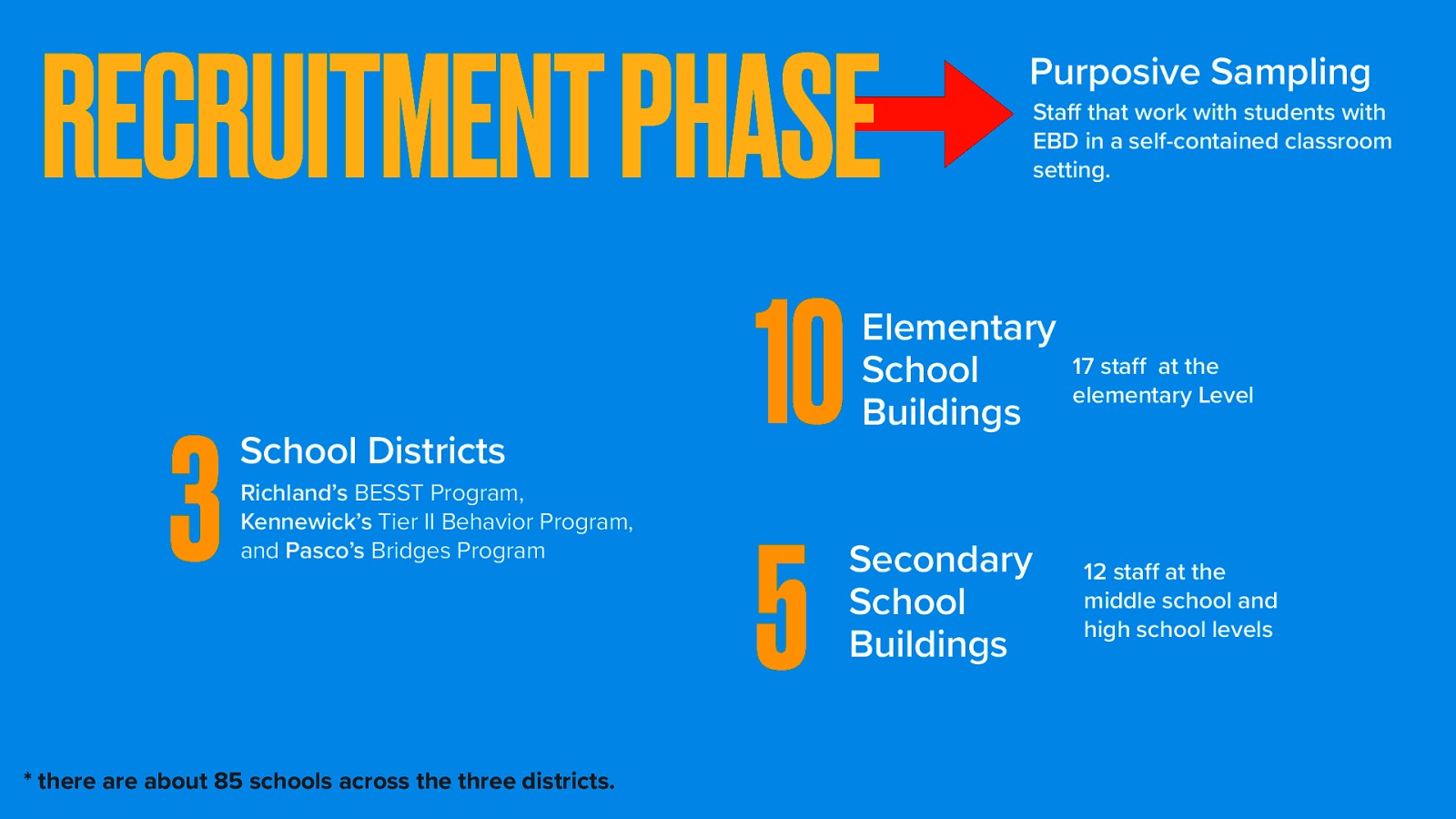

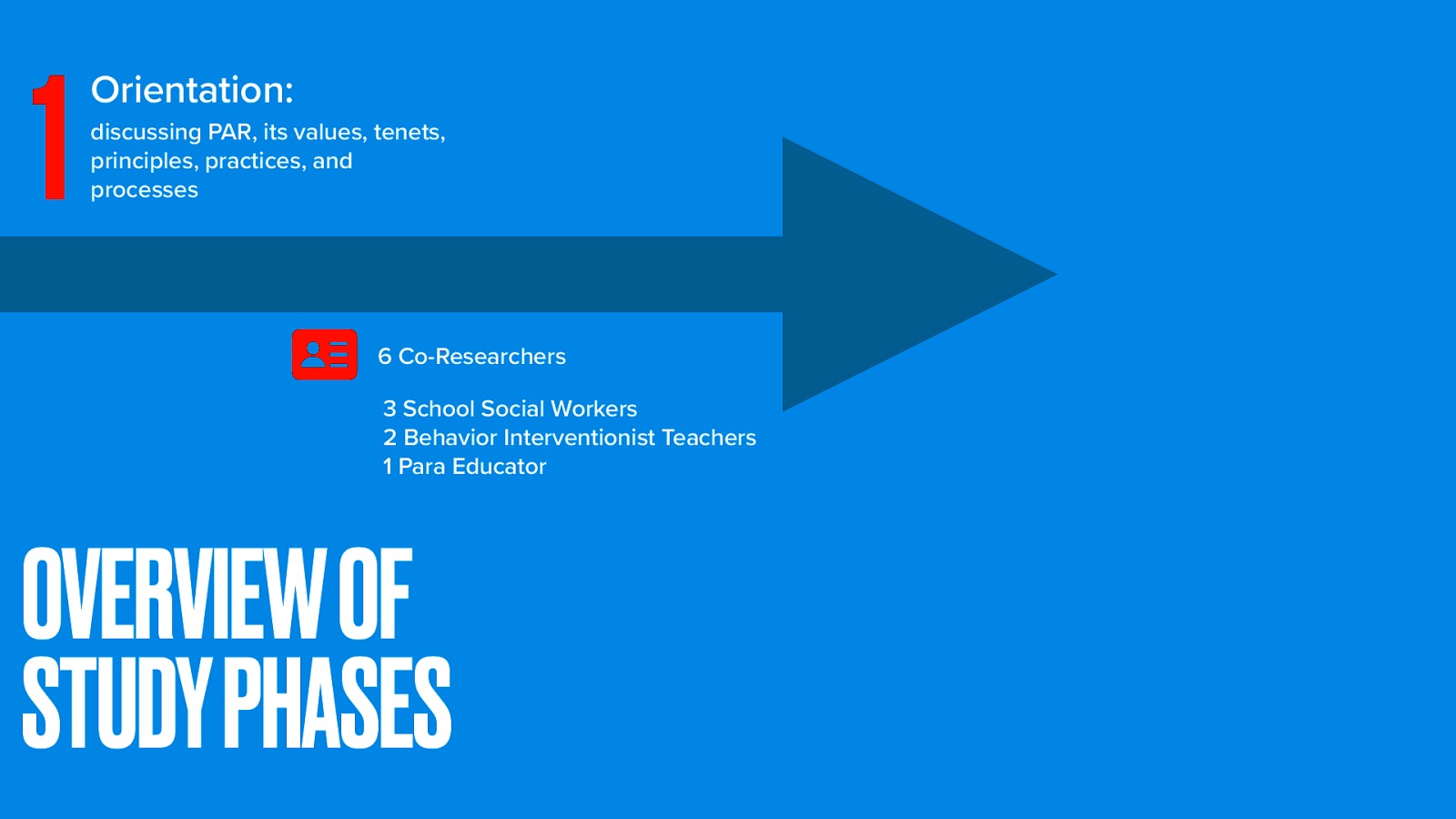

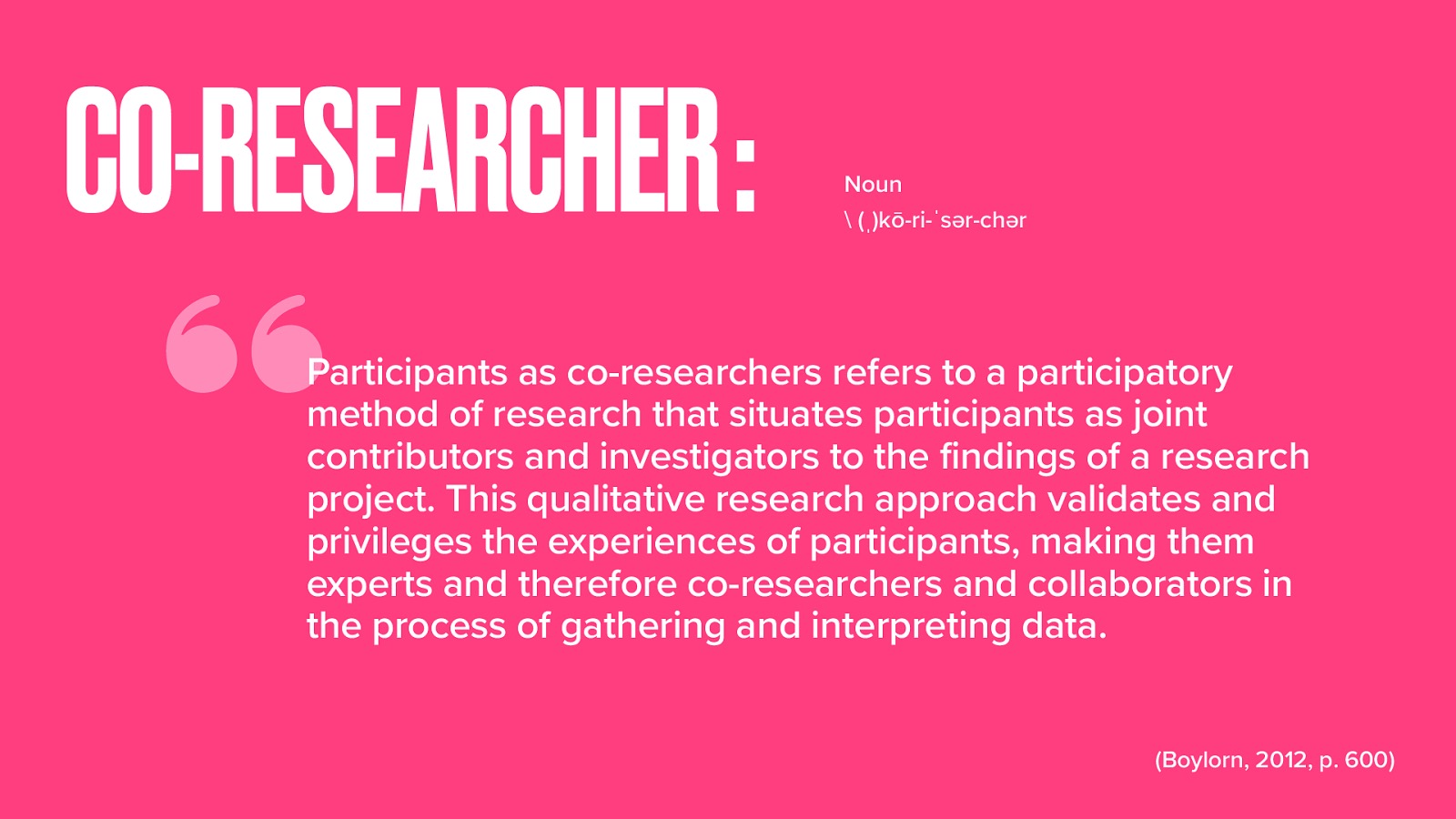

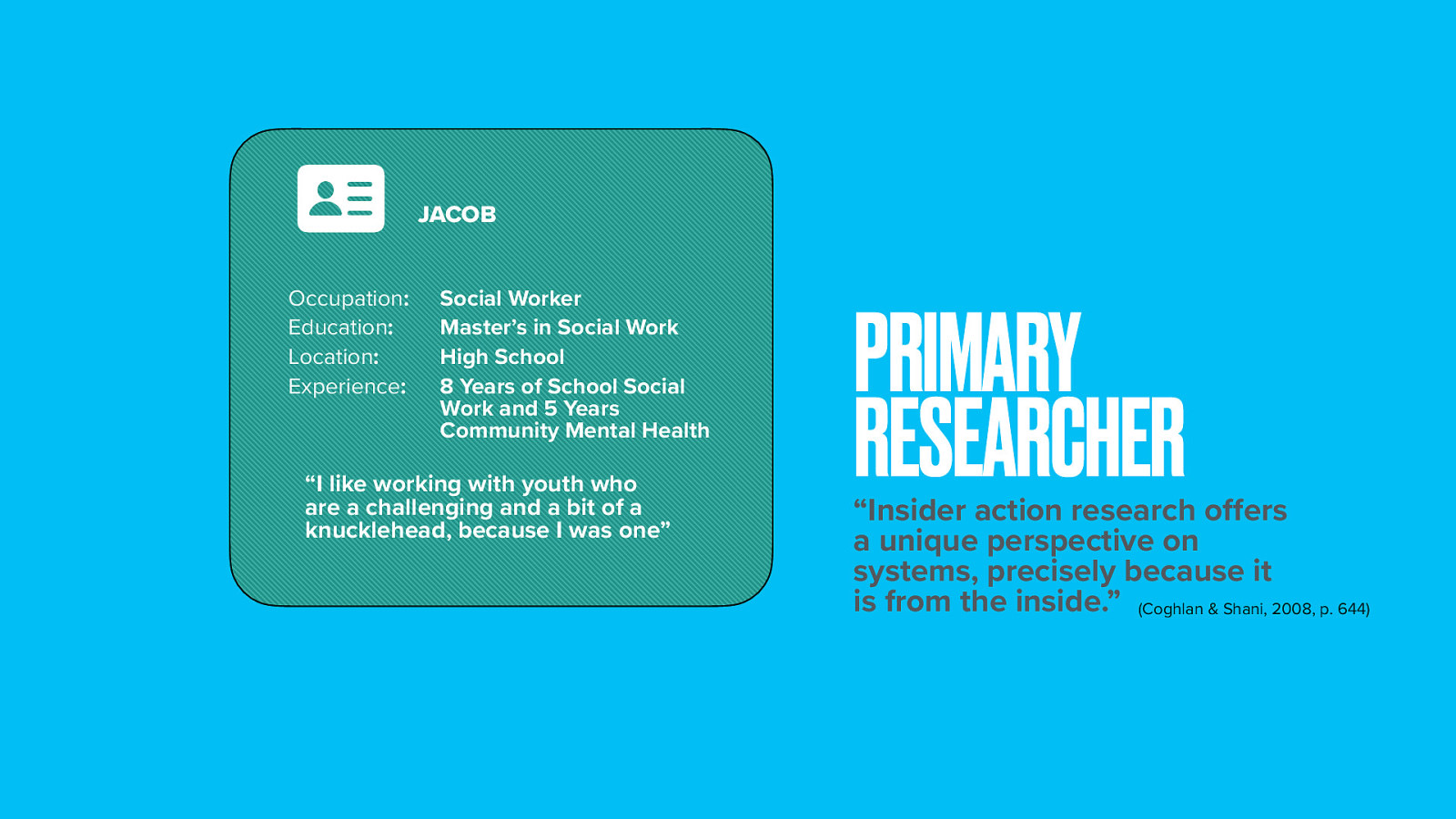

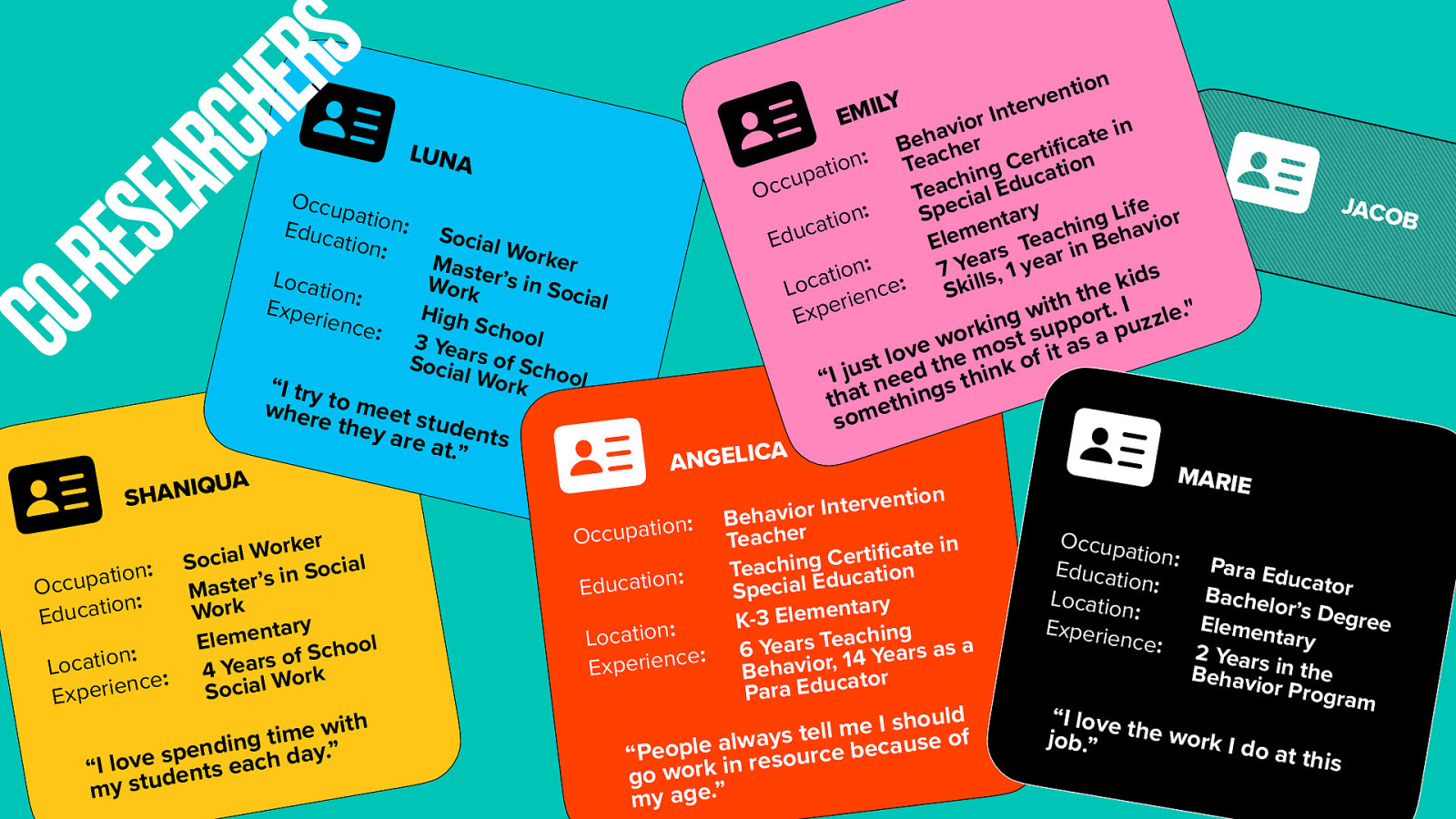

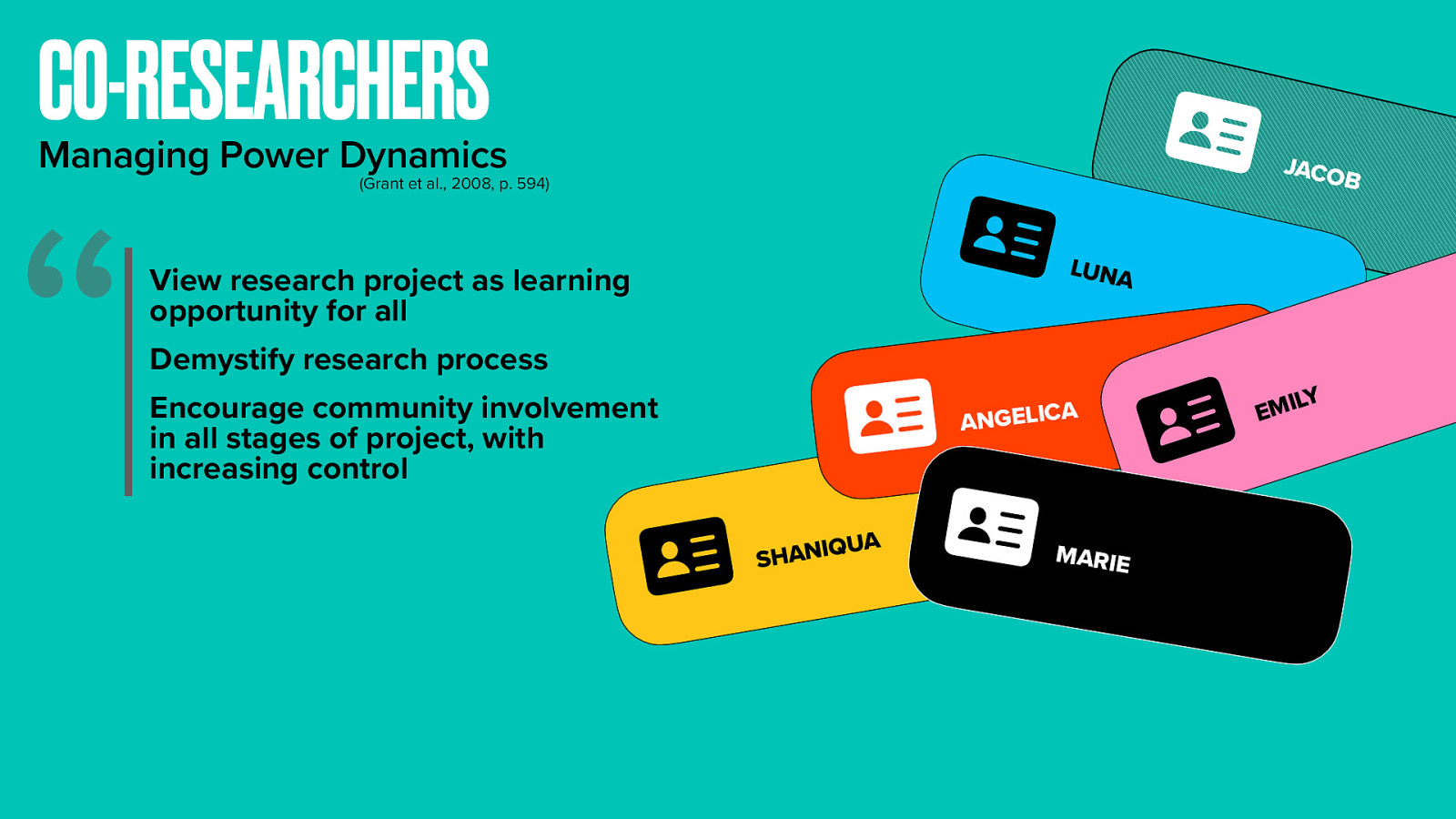

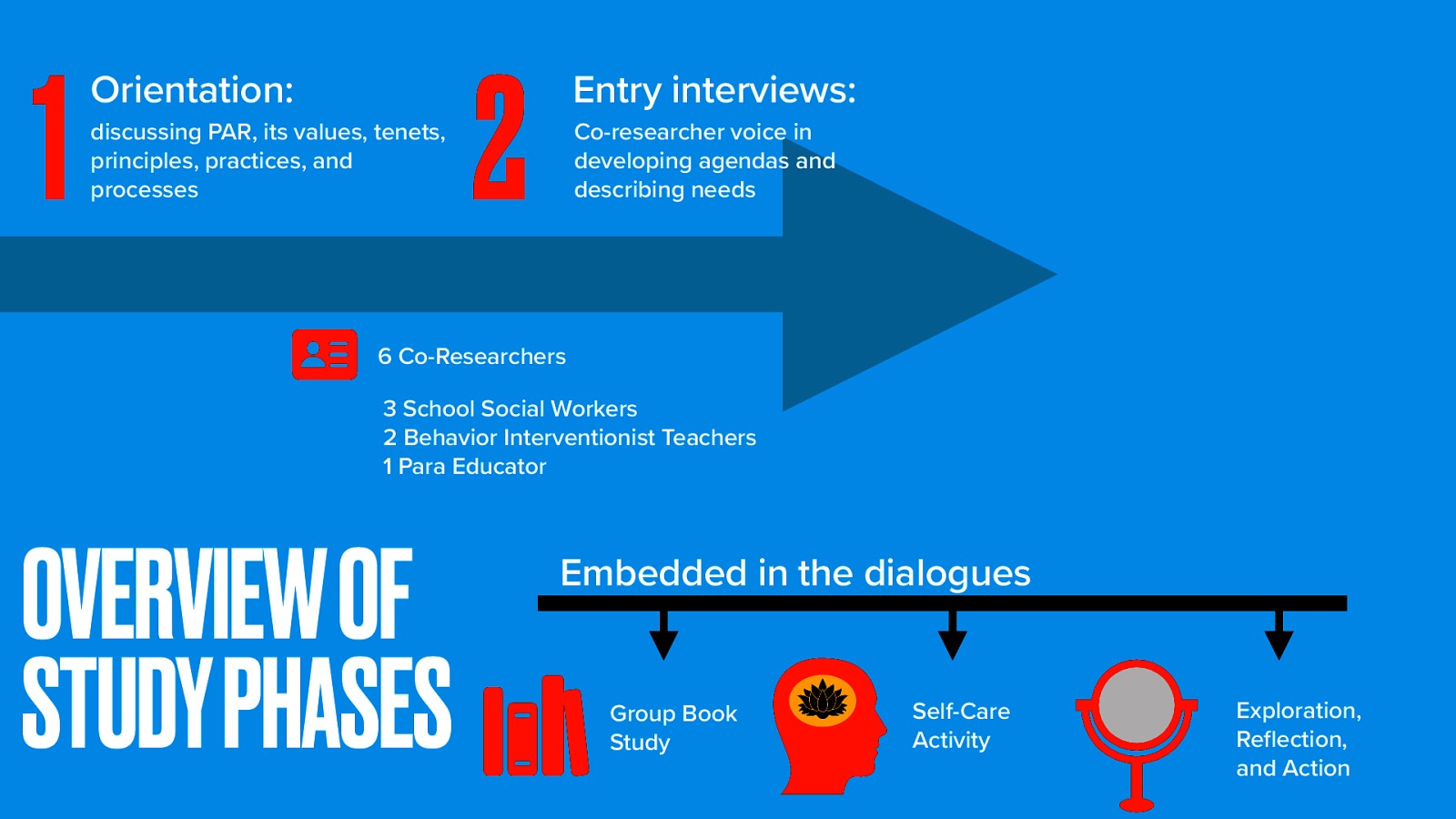

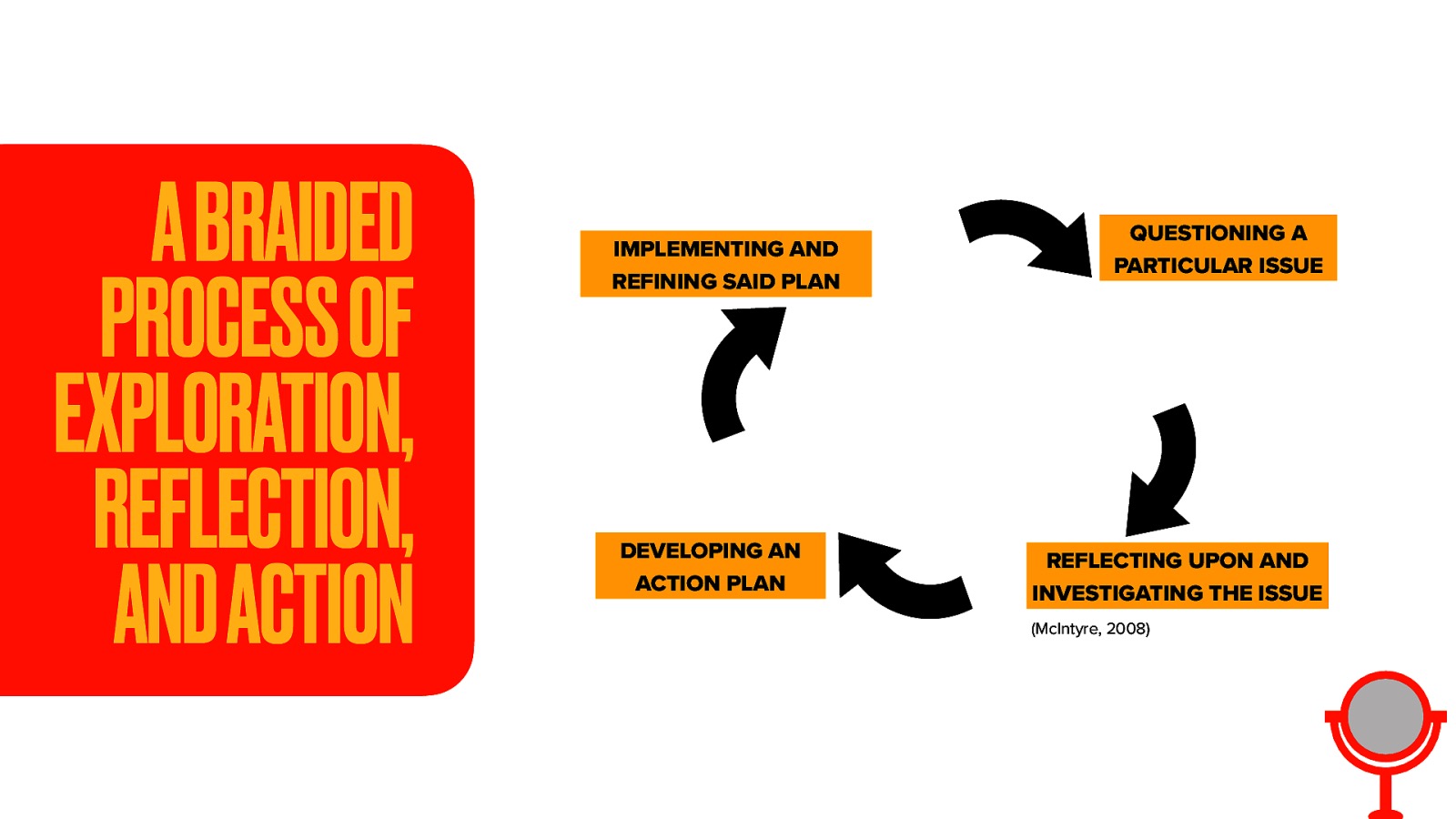

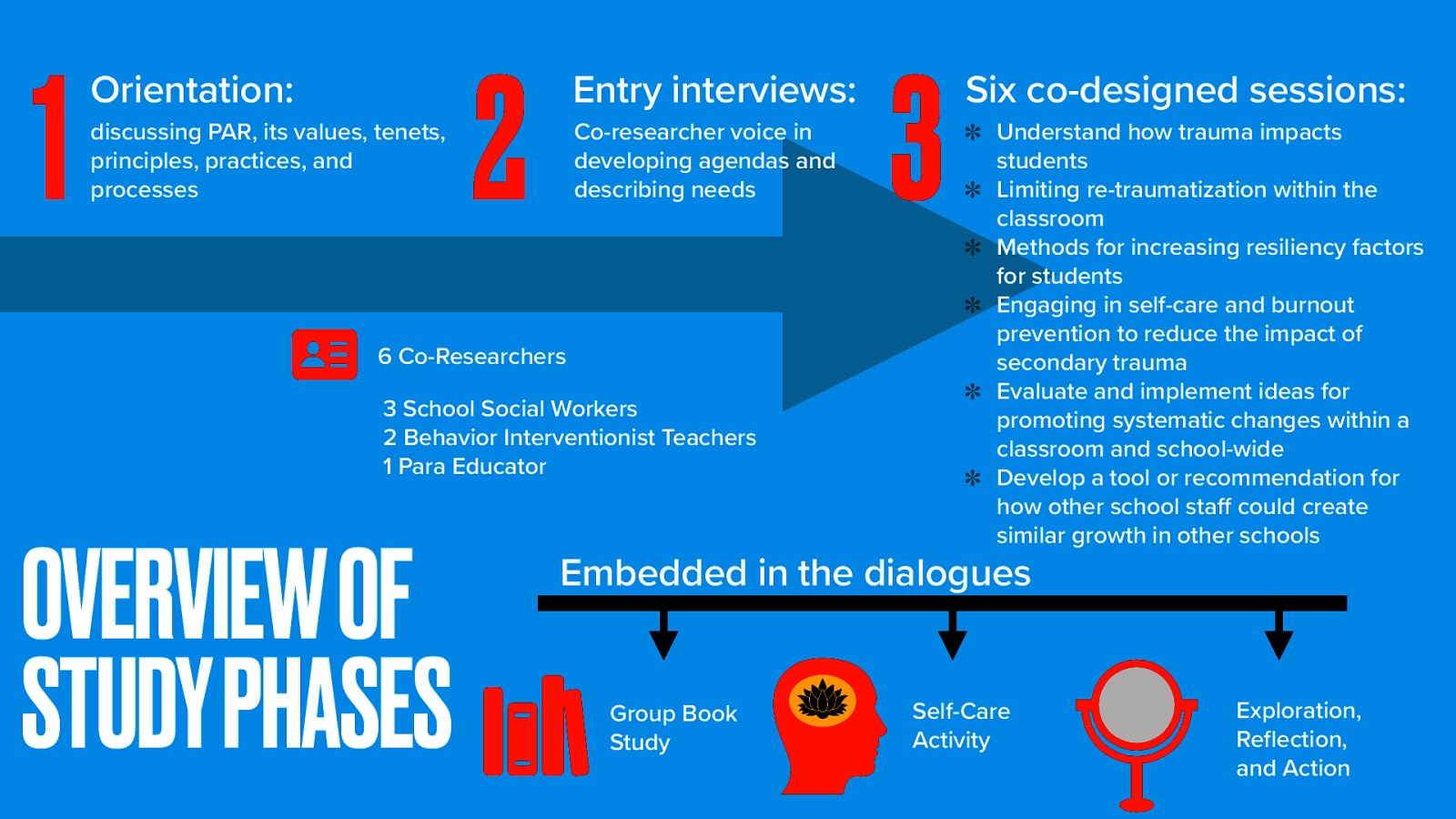

This study uses participatory action research (PAR) methods for a small PLC to explore trauma-informed care practices. This included examining the content and reviewing practice skills. The study co-researchers included six participants working in self-contained special education classrooms that specialize in working with EBD students. The group was comprised of three social workers, two special education teachers, and a paraeducator. The research process included a recruitment phase, orientation, entry interviews, and six dialogues conducted via online video conferencing software. Data collection was the dialogue and activities included in each of these phases. The data included notes from the session, online chat functions, and collaboratively created online documents.

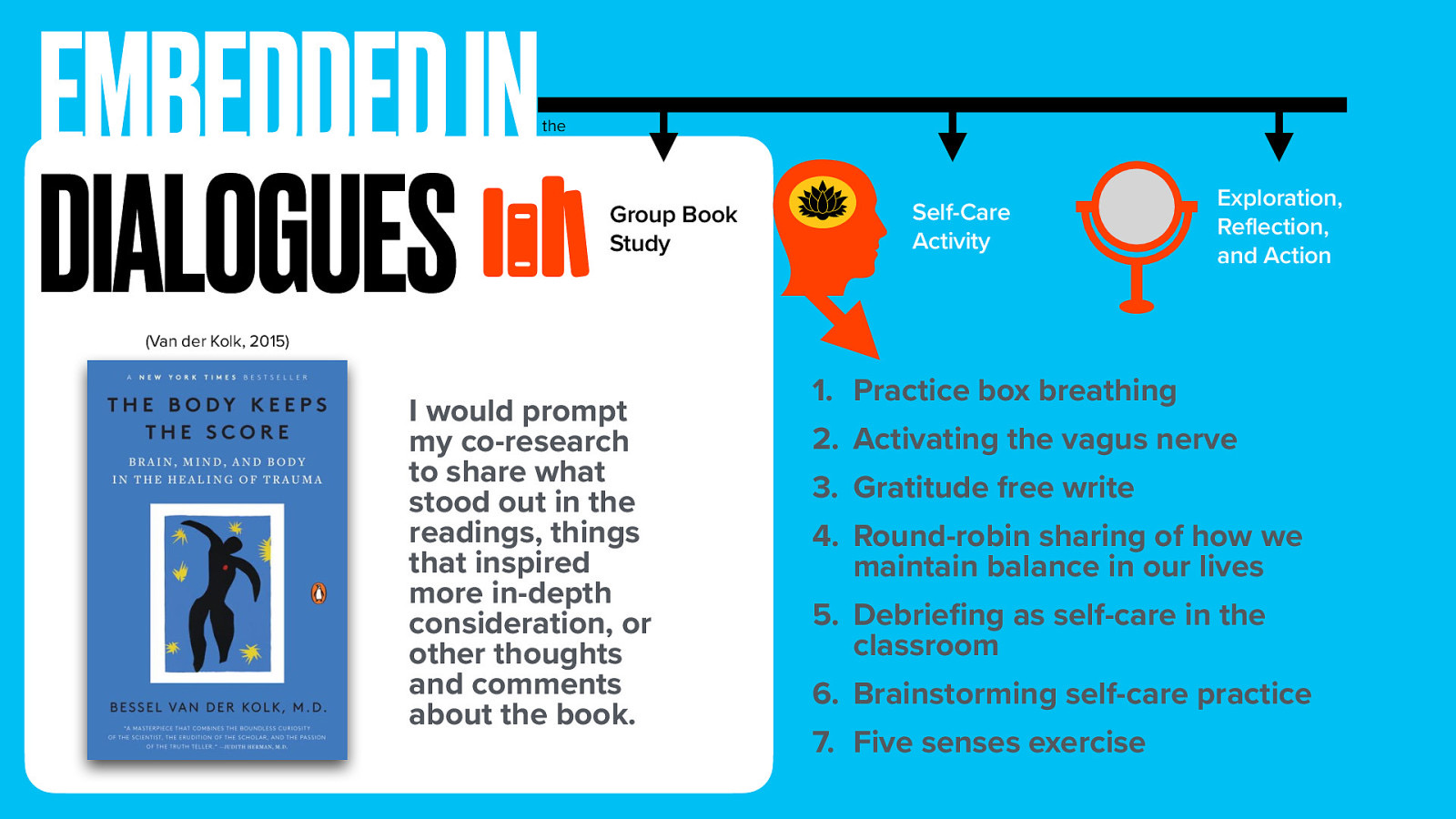

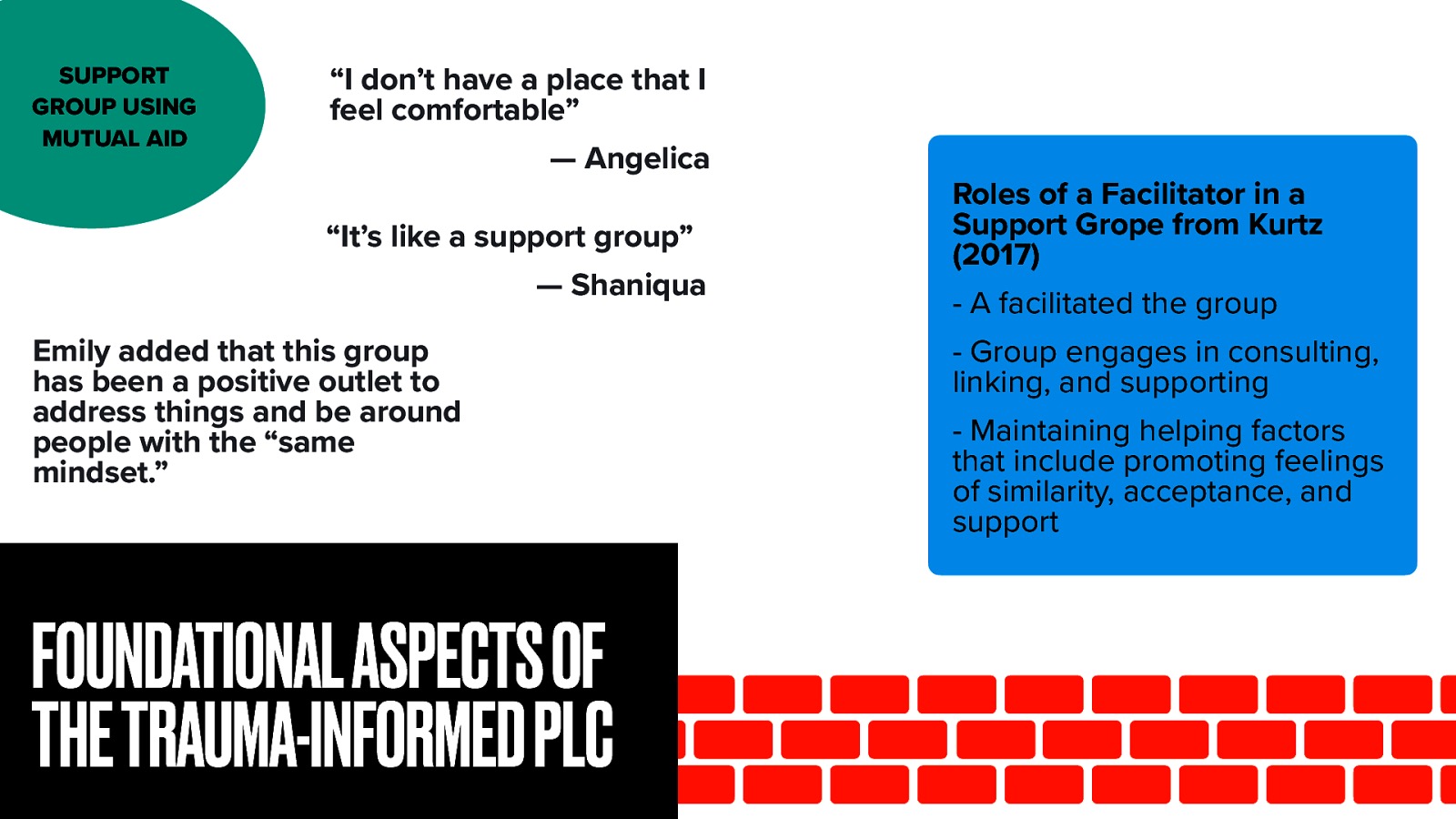

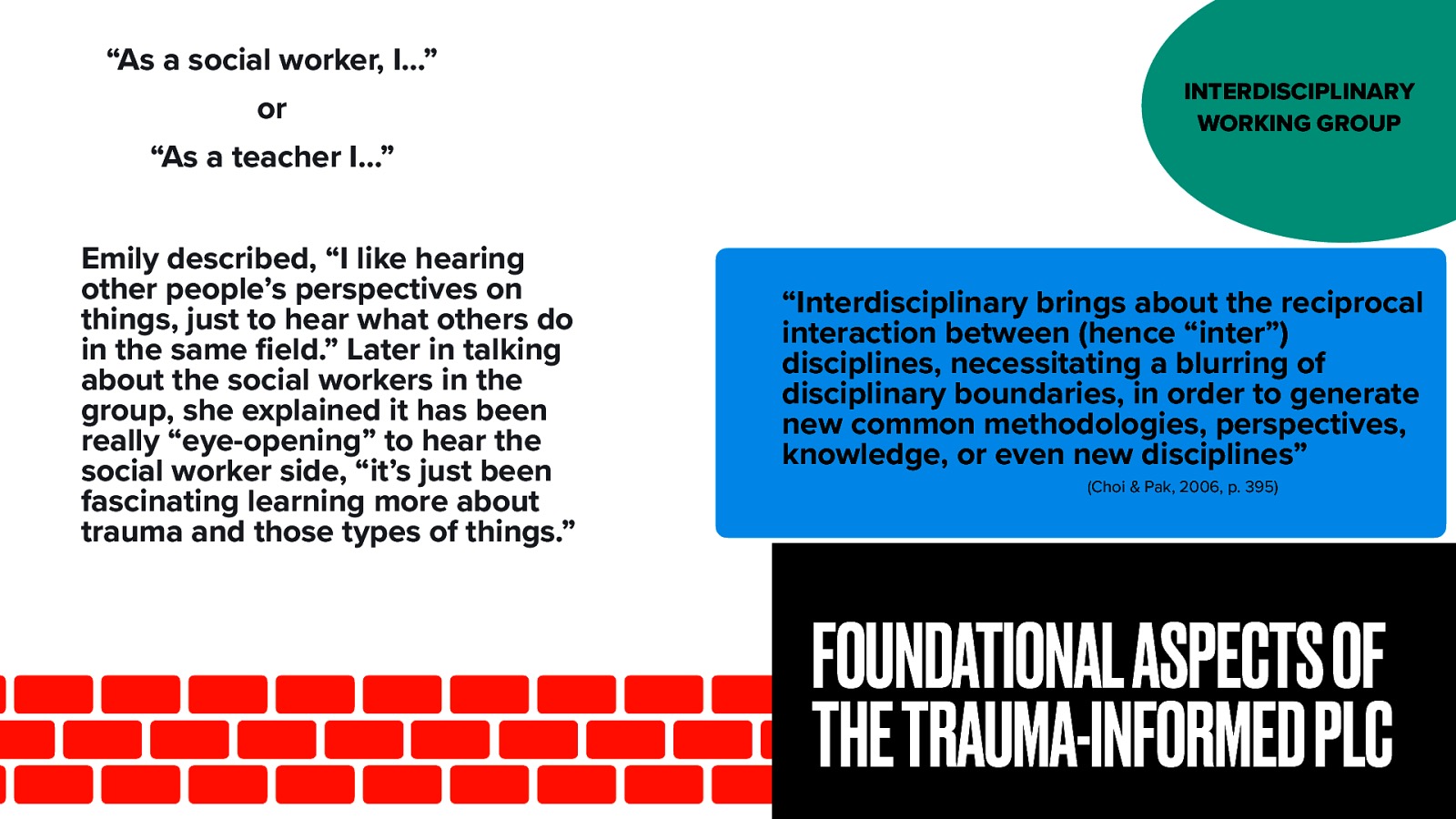

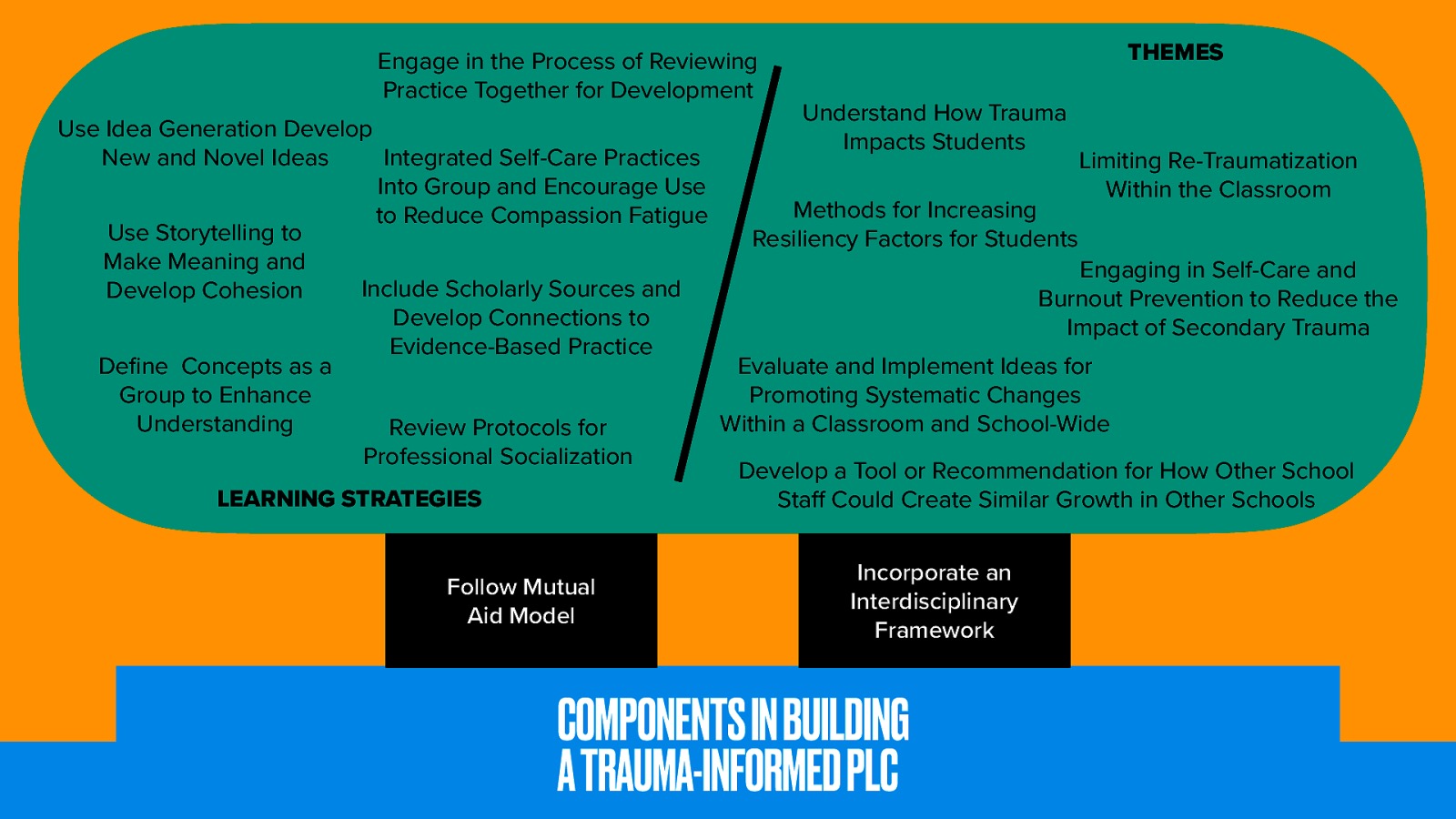

This study was exploratory as it investigated a different way of learning about trauma-informed care. There were a few aspects that are not generally implemented in PLCs. The group followed practices implemented in support groups that use a mutual aid model. The PLC was also interdisciplinary in its functioning and makeup and engaged in professional socialization to improve trauma-informed care practices. Storytelling and idea generation was used to develop an understanding of concepts. Self-care practices were identified and practiced during the group. The members also engaged in a book study to help frame the dialogues.